Repost: A battle for global carbon pricing supremacy is brewing

Why you need to pay more attention to China's carbon market

Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 5,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out the Carbon Risk backstory and find out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow on LinkedIn, Bluesky, and Notes. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents [Start here].

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 9 mins

China’s leaders have publicly pledged to expand their emissions trading scheme in a concerted push to reduce the carbon intensity of the economy.

In a report on the governments progress to the National People’s Congress, Premier Li Qiang outlined how China “will speed up the establishment of a framework for controlling the total amount and intensity of carbon emissions and expand the coverage of the China Carbon Emission Trade Exchange to more sectors.”1

China’s carbon market is far from perfect, targeting carbon intensity rather than absolute emissions. However, it’s telling that as the worlds advanced economies either retreat from global climate policy, or consider postponing their own carbon market ambitions, China is looking to press home its advantage (see Free rider: Carbon border levies could trump US withdrawal from Paris).

As I discuss in the article below (first published in May 2024 behind the paywall), control over the global pricing of carbon is a strategic benefit, one that China seeks to capture.

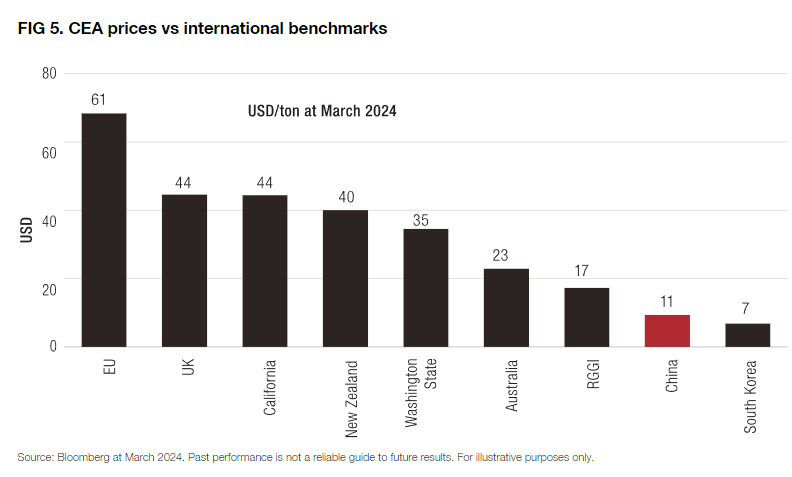

The price of carbon on China’s national emissions trading scheme (ETS) has traded at around €6 per tonne (CNY45) since the market launched in 2021. However, since mid-2023 the China Emission Allowance (CEA) price has doubled as market participants have anticipated a gradual tightening in the market. In spring 2024 CEAs have traded close to €13 ($11, or CNY93.75) per tonne.

It’s good to see the strong performance, but much more needs to be done for China’s carbon price to become a significant driver of decarbonisation. The CEA price would need to rise 4-6 fold to be on a par with more established carbon markets such as the California or EU ETS for example.

Tighter supply and broader industry coverage

As other compliance carbon markets have also found themselves in at a similar stage of development, the Chinese ETS is currently plagued by an oversupply of emission allowances. The London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) estimates total oversupply at 360 Mt CO2 due to generous carbon intensity benchmarks and dodgy emissions data reporting. In response, China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment plans to significantly tighten the supply of CEAs.

First, power generation utilities are expected to see the CEAs allocated to them in 2023 subject to a larger than expected retroactive cut. Second, CEAs that have been hoarded and not used for compliance will lose their value after 2025. The latter is thought to account for around 180 Mt, or half of the oversupply in the market. It means that from 2025 onwards only 2025 vintage CEAs can be used for compliance.

China’s ETS currently only covers the power generation sector, mirroring the early development stages taken by other compliance carbon markets. In total some 2,200 utilities, responsible for 4.5 billion tonnes of GHG per year, or 40% of overall emissions are covered by the scheme. Measured in terms of emissions, China’s ETS is already more than 3 times larger than the EU ETS.

Seven other carbon intensive industries (petrochemicals, chemicals, building materials, iron and steel, nonferrous metals, paper, and aviation), are expected to be included over the next few years. Aluminium (both direct and indirect emissions) and cement producers the most likely short-term candidates. If all of these industries join it would mean that around 70% of China’s emissions are covered by its carbon market. At 7.8 Mt CO2, China’s ETS would balloon to 5 times the emissions covered by the EU ETS.

The regulatory framework for China’s ETS allows obligated emitters to cover up to 5% of their compliance obligation with China Certified Emission Reduction certificates (CCERs). CCERs refers to emissions reduction activities conducted by companies on a voluntary basis that are then certified by the Chinese government. Offset projects can include renewable power generation, waste-to-energy as well as forestry (see Everything you need to know about China's national carbon market).

Based on the markets current industry coverage (and assuming participants used the offset option in full) it would equate to 225 Mt CO2 per annum , or 390 Mt CO2 per annum under an expanded industry scheme. It means that China’s ETS has the potential to become by far the largest compliance-based carbon credit market. As Article 6 develops it could put China in pole position to benefit from global demand for credits.

Time to press its advantage

The next twelve months are significant. By early next year countries must submit their next round of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC), including their 2035 emission reduction targets. One of the key events will be whether Trump returns to the White House in 2025. If he does it could mark another retrenchment in US climate policy momentum. Although that takes the pressure off the Chinese government in some respects, it could be the opportunity for China to press its advantage, and perhaps establish an unassailable lead in global climate policy and delivery (see Climate policy uncertainty is on the rise).

Under an even stronger climate commitment the CEA price is likely to be well supported in the market. DNV has assessed what carbon price is required for China to reach net zero in the late 2040’s. It estimates that China must frontload its ambition and so the CEA price would need to average $100 per tonne by 2030, rising to $200 per tonne by 2040.

China is the worlds largest exporting country and is the biggest trading partner to the EU and the United States. China might recognise that it has an opportunity, in the absence of US resolve to pursue carbon pricing, to become the largest and most important carbon market. China’s ETS could be a counterweight to the EU ETS and eventually supplant the EU ETS as a carbon pricing benchmark used in global trade (see Why Asia is pivotal to future carbon market growth).

A global carbon price benchmark

Although China is currently the largest emissions trading scheme (ETS) based on tonnes of emissions covered, the European carbon market dominates other global compliance markets on a value basis. In 2023 the market traded €770 billion of emission allowances, accounting for around 87% of the global total. The EU carbon price is likely to remain the global benchmark for carbon, especially as other countries move to establish their own ETS’ in response to CBAM.

Nevertheless, there are reasons to suggest that the EU might not have it all its own way. The EU ETS is likely to become much smaller and illiquid over time, particularly towards the latter half of the 2030’s as the EU ETS emissions cap moves towards zero . This could be ameliorated to a certain extent if EU ETS I merges with EU ETS II (the latter due to start in 2027), if carbon removals are integrated into the market, or if the EU ETS expands to include other countries (see Pegger thy neighbour: Why smaller carbon markets link up with larger cap-and-trade schemes).

One factor that it does have in its favour is that emissions are still expected to remain high for decades to come. China is responsible for one-third of global CO2 emissions and although this share is expected to drop to 22% by 2050, according to projections by DNV, China will still exert a significant influence, both with its global climate impact and policies to help tackle it.

Control over pricing

China’s leadership has long recognised the importance of having more control over the pricing of raw materials. As commodity futures prices are used as reference points for physical trading, gaining sufficient market share to achieve benchmark status means that Chinese companies can have a bigger say in the global pricing of commodities.

It’s most recent push has focused on establishing a commodity trading hub for clean energy metals. In July last year the Guangzhou Futures Exchange launched a lithium carbonate futures contract. Meanwhile, the Shanghai Futures Exchange is reportedly working on listing several energy metals including aluminium, recycled lead, magnesium, and tungsten.

China has also began to make it easier for foreign institutional investors to access China's commodity futures markets. This is important since it increases the likelihood that the contract will be widely used as a pricing benchmark. The first commodity futures contract to be ‘internationalised’ was a yuan-denominated crude oil contract, launched in March 2018.

Other commodity futures contracts that have opened up to foreign financial institutions include iron ore, rubber, low-sulphur fuel oil, PTA (purified terephthalic acid), palm oil, and copper. The Chinese carbon market is not open to international investors, but that is likely to change if the experience of other Chinese commodity markets is anything to go on.

Size isn’t the only thing that matters

Worries about declining liquidity have a parallel in commodity markets. The Dated Brent crude oil benchmark index is four decades old but has arguably been one of the most important numbers in the global economy; two-thirds of the 100 million barrels of oil traded each day derive their value from the benchmark.

Originally based on the UK’s Brent field, three Norwegian oil fields plus one other UK field were added to the index in 2002 to counter liquidity worries based on the long-term decline in Brent production. UK and Norwegian oil production is in long-term decline, and so in 2023 the decision was taken to add WTI Midland to the Dated Brent basket of crudes. So far at least it appears the latest iteration of Dated Brent is working well. It shows that benchmarks must evolve if they are to remain useful.

As the experience of Dated Brent and other commodity benchmarks shows, to gain credibility a benchmark must tick many boxes, and having sufficient production of the underlying commodity is only one of them. In the example of crude benchmarks some are dominated by a single or a limited number of buyers or sellers, others are impaired by distorting tax regimes, while many pretenders to the throne are vulnerable to weak legal protection and political interference.

A battle for global carbon pricing supremacy is brewing.

👋 If you have your own newsletter on Substack and enjoy my writing, please consider recommending Carbon Risk to help grow this amazing community of readers! Thank You!👍

http://www.npc.gov.cn/jzzqw/jzzq/c34155/202503/W020250305326603076336.pdf