Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 3,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow my posts on LinkedIn. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents.

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 7 mins

At least one carbon market is considering linking up with a larger, more established emissions trading scheme.

Washington State has only been in operation for a little over 12 months, but there is already pressure to establish a link with the Western Climate Initiative (WCI) that counts California and Quebec as its members. As discussed in The spectre of 'gilets jaunes' returns, high carbon prices are at least partly to blame for an increase in gasoline prices in the Pacific state. At least until speculation over the future of Washington State’s carbon market sent its carbon price into a tailspin, the price of emission allowances in the state were almost double the prevailing price in California.

Meanwhile, industrial emitters in the UK have been lobbying to link up with the EU ETS. In contrast to the situation in Washington State, UK manufacturers gripe is a function of carbon prices being too low in the UK relative to the rest of Europe. First off they are concerned that low carbon prices could have a detrimental impact on investment in decarbonisation in the UK. Secondly, the low carbon price will also negatively affect UK exports to Europe when the EU’s CBAM is gradually phased in from 2026. Recall that the cost of meeting CBAM is based on the relative difference in carbon prices between the EU and the exporting nation (see No level playing field: Europe's carbon levy will accelerate adoption of carbon pricing, but not everyone will win).1

An election in the UK is expected to take place in the autumn. The UK and the EU are likely to enjoy a closer relationship under a Labour government, and could look to begin negotiations on linking up. The European Commission would need to get a mandate from the Council and Parliament before negotiations on an international treaty, such as the one agreed with Switzerland, could proceed. Speaking to OPIS, a spokesperson from the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) stated that the UK maintains an open position to linking to the EU ETS:

“We are open to the possibility of linking the UK ETS internationally and will continue to work collaboratively with other jurisdictions to tackle shared challenges and learn from the experience of others as we develop the scheme.”

Although there only a few examples of carbon markets linking up with another, the limited sample does give an indication of what we might expect.

Quebec launched its carbon market in 2013, but after only one year it linked up with California under the WCI. The linkage process was relatively seamless as both jurisdictions are sub-national (avoiding complications such as Article 6 of the Paris Agreement), while Quebec’s ETS had been constructed based on the California blueprint, and so was already pretty well harmonised.

A harmonised approach to ETS design meant that Quebec’s linkage with California meant little in the way of redesign was necessary. The same is likely to hold true for both Washington State and the UK ETS should they link with their larger, more established carbon market neighbours. The former was designed with the potential for linkage in mind, even before it was launched. The latter split from the EU, closely mirroring the EU ETS in its design. The two markets have developed along similar lines and have also explored broadly comparable iterations (e.g. including carbon removals), albeit on slightly different timescales. The closer the two markets develop in a coordinated fashion, the easier it will be to link up at some point in the future (see UK carbon market nadir has passed).

Another important lesson from Quebec’s linkage with California is that the relative size of the two markets is the most important factor in price formation. Carbon prices in Quebec (prior to linkage) had consistently been lower than California, despite a high share of renewables in the generation mix and fewer low-cost emissions reduction opportunities. When Quebec established a link with California (whose carbon market was ~6 times bigger), carbon prices moved higher to align with the price in California. If Washington State does seek to establish a link with California, it’s worth noting that Californian Carbon Allowances (CCA) are now much higher (up ~60% versus early 2023), limiting the potential for cost savings.2

The act of linking your carbon market to a larger, more established market can be thought of as a country pegging its currency to the US dollar or a basket of currencies. By tying their hands, governments pursuing this strategy bolster their economic credibility with the market, often enabling domestic industry to benefit from lower capital costs than would be present otherwise

Although linkage reduces the opportunity for asymmetric action that might weaken the carbon price, it also comes at a cost. As we’ve seen it can result in a higher carbon price, which might be too high for the domestic industry to bear. Linkage could also import carbon price volatility if political changes in the larger ETS introduce uncertainty. Finally, it could also result in financial flows out of the country, especially if decarbonisation is more efficient in the larger ETS.

Not all linkages go well, and like a prenup might prevent a married couple from going to war, having a plan in place should parties decide to split tends to help market stability. For example, much less well known is that Ontario, the largest Canadian province by GDP and twice as big as Quebec, also established a linkage, albeit a brief one, with California-Quebec in 2018. The election of a new premier in June that year resulted in a change of heart as Ontario’s participation was deemed to be a bad deal for the province. On the day that Ontario announced the split, the WCI temporarily suspended the trading accounts of emitters based in the province preventing the allowances from being dumped on the market.

A more recent example is the state of Virginia’s and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). The state’s Democratic lawmakers voted to join RGGI in 2020, joining almost a dozen other states in the northeast US. However, a change in political leadership in 2022 led to the Republican leader seeking to remove Virginia from the scheme, citing higher energy costs for consumers. Over two years later the state remains in a legal stalemate, with neither supporters or detractors seemingly able to secure the state’s future (see Volatile RGGI carbon prices as Virginia's Governor continues to push to leave the scheme).

The first international carbon market linkage to occur was between the EU ETS and Switzerland’s ETS (set up in 2008). Beginning in 2011, it took 6 years to finalise negotiations on linking the two schemes. A referendum on anti-EU immigration legislation in 2014 prompted retaliation from the EU in other areas of cooperation which slowed down negotiations. However, it wasn’t until 2020 that the linkage actually became operational. Under the terms of the linking arrangement, Switzerland's system remains separate from the EU ETS, rather than joining it as a participating country, but there is two-way fungibility of EU and Swiss emission allowances.

In the early 2010’s the EU had indicated it was willing to discuss linking its ETS with other compatible schemes elsewhere in the world. Improved market liquidity, more cost-effective emission reduction, and lowering the risk of carbon leakage were seen as the main benefits. The EU had even agreed a pathway for linking with Australia’s fledgling carbon market by 2018, before a change in political leadership in 2013 and a move towards less ambitious climate policies scuppered those plans. Other countries where the EU had increased its technical cooperation included South Korea and China, although any direct link was always thought to be several years away, if ever.

Other than the UK ETS potentially linking with the EU ETS, it is very unlikely that any other country currently fits the bill, and its unlikely that there would be much appetite for it from the EU. Rather than pursue an expansion in the EU ETS to achieve improved liquidity, reduce costs, and lower leakage risk, the more likely scenario is that the EU looks to its CBAM, coupled with promoting the adoption of carbon markets among its trading partners, as a more suitable way to achieve those same benefits.

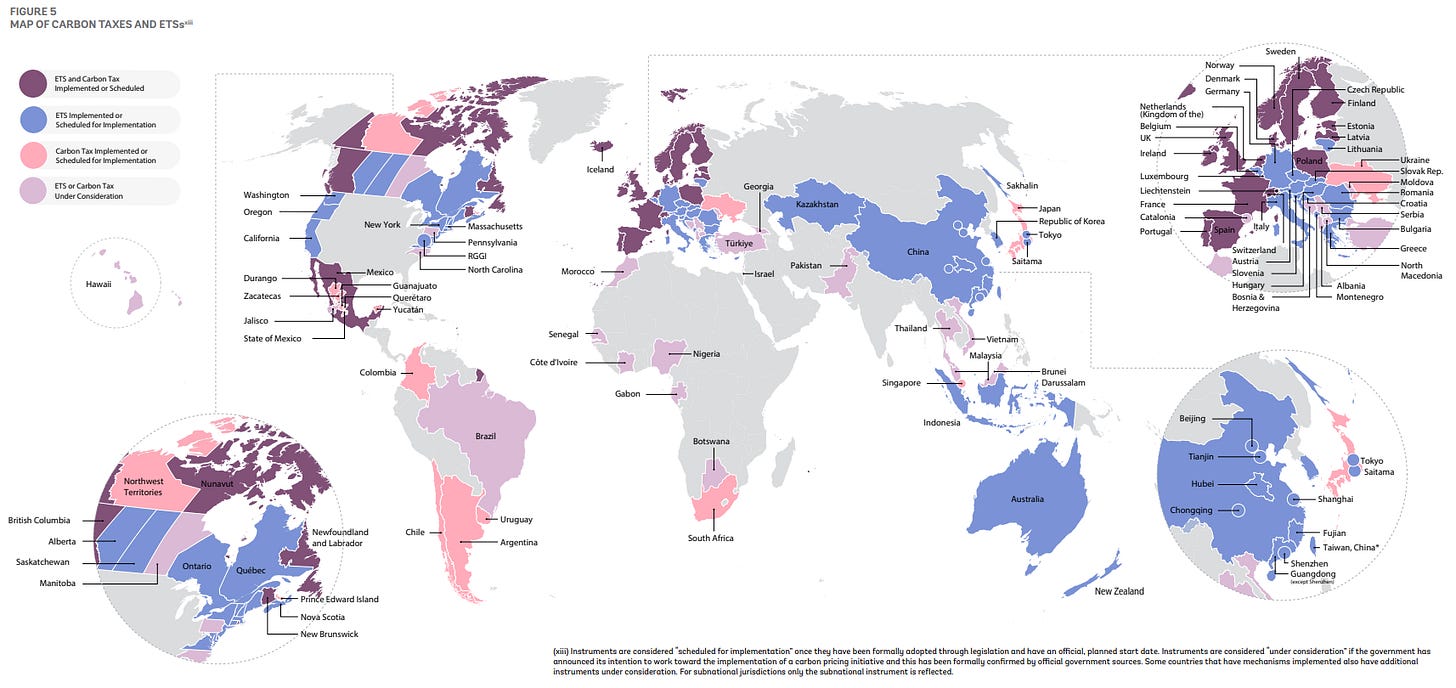

Carbon markets are going global

“The answer to the global climate crisis is carbon pricing.” - Kurt Vandenberghe, the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Environment (DG ENV) Carbon pricing plays a number of roles including internalising the cost of negative externalities resulting from greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and putting a price on the remaining carbon budget consist…

https://www.energy-uk.org.uk/publications/without-linking-emissions-trading-systems-uk-companies-face-higher-bills-and-red-tape/

https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Vivid-Economics-The-Future-of-Carbon-Pricing-in-the-UK.pdf