“The answer to the global climate crisis is carbon pricing.” - Kurt Vandenberghe, the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Environment (DG ENV)

Carbon pricing plays a number of roles including internalising the cost of negative externalities resulting from greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and putting a price on the remaining carbon budget consistent with achieving a certain temperature objective.

It acts as a signal to consumers about which goods and services are carbon-intensive. It signals to producers of products and services which inputs and activities they should switch towards to reduce their carbon costs. It also fosters innovation and entrepreneurship by signposting that demand for low carbon alternatives are likely to rise.

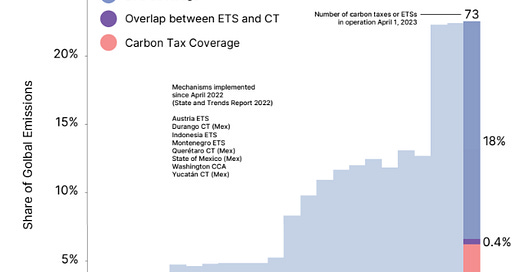

Yet currently less than one-quarter of global emissions are covered by some form of direct carbon pricing according to estimates from the World Bank; 18% is covered through emissions trading schemes (ETS) also known as cap-and-trade, carbon taxes cover 5.5%, while 0.4% is covered by both an ETS and carbon taxes.1 2

There have been three major step changes in terms of coverage since the year 2000. The launch of the EU ETS in 2005 marked the first step (initially covering ~5% of GHG emissions). The advent of California’s carbon market in 2012 was the second step. Over the rest of the decade carbon pricing only expanded incrementally. The most recent and the single largest step in carbon pricing occurred in 2021 following the launch of China’s ETS (initially covering ~40% of its annual GHG emissions).

In 2022 almost $100 billion of fiscal receipts was raised by governments from carbon pricing with ETS’ accounting for around two-thirds of the revenue raised. According to the Institute for Climate Economics, 40% of the total revenue was earmarked for dedicated purposes such as green investment, 20% formed part of general taxation, 10% was recycled and used to support those households and firms adversely affected by carbon pricing, tax cuts were funded using 9% of the revenue, while the remainder used for other purposes.

While carbon taxes involves controlling the price of carbon and letting the market decide the emissions response, an ETS controls for emissions (by setting a cap) and lets the market decide the price. The greater the share of global emissions covered by cap-and-trade carbon pricing the better.

From 18% in 2023, the percentage of global GHG emissions covered by ETS’ is expected to grow substantially over the next decade. The president of the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA) recently estimated that around two-thirds of global emissions could be covered by an ETS by 2030.3

In 2022 the global traded market in emission allowances reached in excess of $900 billion according to Refinitiv, an increase of 14% on 2021. The EU ETS, the worlds largest carbon market by value traded around $750 billion in emission allowances last year. Scaling up based on recent carbon prices and trading activity suggests that carbon allowances could be a $3.3 trillion market by the end of this decade (see Is the VCM a trillion dollar business opportunity?).

One of the biggest issues with the current patchy coverage is ‘carbon leakage’. This occurs when firms located in a region subject to carbon pricing loses market share to more carbon intensive imports, or where a carbon intensive firm (or even a whole industry) seeks to move its operations to a jurisdiction with less onerous environmental regulations.

The risk of ‘carbon leakage’ limits the effectiveness of carbon pricing. Consumers may decide to import cheaper products from jurisdictions not subject to carbon pricing, while producers may decide not to invest in new low carbon technology if the demand for innovative products and services is likely to be limited, or subject to extreme uncertainty.

The imminent launch of Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) seeks to address ‘carbon leakage’ by ensuring importers of carbon intensive goods account for the negative externality by paying a levy. Other jurisdictions including the UK, Australia and the US are all considering introducing their own version of the EU’s carbon levy.

The CBAM is fast becoming one of the main drivers towards a greater share of global emissions being covered by carbon pricing. As I outline in No level playing field, “The only way to avoid buying a CBAM certificate [the equivalent to an emission allowance] is if the country of origin has the same climate ambition as the EU. It follows that the CBAM should act as an accelerant for global climate ambition and the adoption of carbon markets as an instrument for decarbonisation.”

Earlier this year the World Bank launched a tool to help identify those countries most exposed to the CBAM. Their aggregate relative CBAM exposure index calculates the sum of the total excess embodied carbon payments, divided by the sum of the country's total value of exports of CBAM products to the world. The deeper the orange colour in the map below, the higher an individual country’s aggregate relative CBAM exposure. Three of the most heavily exposed countries - all substantial contributors to global emissions - look set to introduce carbon pricing gradually over the next few years - Indonesia, Brazil, and India.4

In February 2023, the Indonesia government launched the first phase of their emissions trading scheme as the largest coal powered electricity generators (those with a capacity of at least 100MW) began bilateral trading of allowances. In late September the carbon exchange was formally launched enabling a much deeper pool of liquidity to develop. The government is reportedly considering expanding the cap-and-trade scheme to also include forestry, industrial processes and product use, agriculture and waste management (see Commodity markets begin to price carbon risk).

Brazil is the most recent country to announce its carbon pricing plans. Although not quite as exposed as some countries, Brazil is a significant exporter of iron and steel to the EU. Although the exact scope of industries included in its ETS is yet to be confirmed, it’s thought unlikely to affect the agricultural and forestry sector despite them being responsible for the lions share of Brazil’s emissions and the leading cause of deforestation. Around 5,000 carbon intensive companies, primarily from the oil and gas, chemicals, steel, and cement sectors are thought likely to be impacted by the legislation once it has been implemented. After a interim reporting period of 1-2 years, the scheme is likely to start in full around 2028/29 (see Repricing deforestation risk in the wake of Brazil's presidential election).

India is a notable omission from the earlier map of carbon pricing initiatives, but that could be about to change. Reuters reported in October that the government are planning on introducing an emissions intensity based carbon trading scheme (similar to how the Chinese ETS works). The article suggests that the targets will be introduced in 2024/25 with trading of carbon allowances beginning in 2025/26. The sectors included in the ETS are expected to be petrochemicals, iron and steel, cement, and pulp and paper. As I highlight in Inflexion point: The Indian economy is pivotal to the future direction of global carbon emissions, India is not new to environmental markets. However, they have yet to gain a foothold across large parts of the economy. But with India expected to be at the centre of global energy demand growth over the next couple of decades it will need to introduce carbon pricing quickly if it is to meet its net zero commitments and reduce its CBAM exposure.5

Extending carbon pricing to cover the rest of the world’s emissions is likely to be a key discussion point at COP28 in Dubai this November and December. In recent weeks European and African leaders have called for a global carbon pricing to help channel capital to less developed economies and help them accelerate their own net zero energy transition. However, any meaningful increase in carbon pricing coverage could impose a high short term cost on those economies (and sectors of society) that are fossil fuel intensive. Mitigating the regressive nature of carbon pricing will be key to accelerating the global adoption of emissions trading, especially as governments come under pressure to water down or even drop net zero policies (see Collateral damage revisited).

To that end governments need to recycle a much greater proportion of the funds raised by carbon pricing back to those who are adversely affected. As I explained earlier in this article, only 10% of the revenue raised by carbon pricing is currently recycled back to vulnerable parts of society. Transfers need to take the form of transparent cash transfers (being clear on the source of the funds should engender support for the carbon pricing policy), while also offering generous incentives to help them mitigate their carbon exposure (e.g. funding heat pumps, solar panels, insulation, etc.).

Three decades ago the United States introduced a sulphur dioxide emissions trading scheme covering the country’s power plants. The scheme was the first in the world to put a tradable price on pollution and its success in cutting emissions set the stage for the development of the European carbon market and subsequent ETS’. Today, those same market concepts are being used to signal where to cut carbon emissions, while allocating scarce resources in the most efficient way possible. It’s time that all governments took heed of that signal and seek to rapidly expand emissions trading to cover a much greater proportion of global emissions.

Carbon markets are going global. You don’t want to be left behind.

The great sulphur dioxide allowance bull market

The EU’s carbon market was not the worlds first cap-and-trade system to tackle a serious environmental problem. That honour goes to the United States sulphur dioxide (SO2) allowance trading system. Flue gas emissions from coal-fired power generation released huge quantities of sulphur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions high into the atmos…

https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/58f2a409-9bb7-4ee6-899d-be47835c838f

Indirect pricing of carbon is far more prevalent than the direct pricing methods discussed in this article. For example, governments often put a price on carbon indirectly through gasoline and diesel taxes, fossil fuel heating levies, and renewable energy price premiums, etc. The production and consumption of fossil fuel is also subsidised in many parts of the world, indirectly pricing carbon as a negative value. The net average effective carbon rate (ECR) is a way to aggregate the overall impact of these policies (direct and indirect, positive and negative) into a single price (see Fuelling controversy: Fossil fuel subsidies act like a negative carbon price).

https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/032723-interview-net-zero-goals-changing-global-politics-carbon-markets-in-for-a-bumpy-ride-ieta

https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2023/06/15/relative-cbam-exposure-index#4

https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/india-set-emission-reduction-mandates-4-sectors-start-carbon-trading-2025-2023-09-26/

Hi NM. KRBN and GCO2 allocate 5-10% to the UK. I haven't seen anything higher than that https://carbonrisk.substack.com/p/how-to-start-investing-in-the-eu

Peter are you aware of any investment vehicles that track UKAs? either through IG or ETF? or else? i have the impression you have supplied some in the past.