Inflexion point

The Indian economy is pivotal to the future direction of global carbon emissions

India is expected to be at the centre of global energy demand growth over the next couple of decades.

Emerging from the shadow of its regional rival on the other side of the Himalayas, India is now the most populous country in the world. India is the fifth‐largest economy in nominal terms, behind the United States, China, Japan and Germany.

The Indian economy grew at an annual average rate of 5.5% during the decade to 2021, while at the same time reducing its emissions intensity of GDP by 1.3% per annum to 1.5 kg of CO2e per $ per annum. Ever so slightly it is decoupling its emissions from economic growth.

Yet despite its strong growth and sheer size on an aggregate basis, India remains someway behind other countries on a number of per person metrics. Whether its energy demand, steel and cement use or car ownership, India has the potential to grow significantly according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). And grow it should. Remember, the underlying purpose of economic development is to lift people out of poverty.1

India’s economy is at a crucial inflexion point

India’s energy needs are expected to grow at three times the global average under today’s policies as urbanisation fuels a construction boom, consumers increase purchases of air conditioning (AC) systems and hundreds of millions of vehicles hit the roads.

The speed at which urbanisation has occurred in India has been much slower than other East Asian industrialising countries. Even under the IEA's central scenario based on India's existing policy mix, urbanisation is only expected to reach 46% by 2040. That is much lower than comparable countries in percentage terms, yet in absolute terms this will be equivalent to adding 13 cities the size of Mumbai over the next twenty years.

Much of the slow uptick in urbanisation relative to other countries has been due to agricultural policies such as subsidies (accounting for ~4% of GDP) that discourage the movement of people to more productive jobs in the city. The recent protests by Indian farmers, distrustful of market reforms are a sign that India could be near the tipping point where urban growth and overall economic growth starts to take off.

Known as the 'Lewis turning point', it is the point at which economic development where surplus rural labour is fully absorbed into the manufacturing sector. This typically causes agricultural and unskilled industrial real wages to rise. However, in a country where over 40% of the workforce are employed in agriculture, those farm workers represent significant political clout, which can block reform.

The process of urbanisation is initially extremely commodity intensive and once completed it then locks in very high levels of energy consumption. For example, first it generates demand for steel, cement, copper and other commodities. And then once built city dwellers tend to spend more of their income on energy - specifically the cost of travelling around the city. Because of the huge sunk costs involved in building out this infrastructure, energy consumption patterns tend to get locked in over a long period of time (see Concrete returns: Laying the foundations for a decarbonised cement industry).

Urban dwellers also tend to purchase more appliances (TV's, refrigerators, washing machines, etc.) to furnish their flats, which then consumes more and more commodities on an ongoing basis. In a hot country like India the share of households with an AC unit stands at less than 10% in urban dwellings and negligible in rural areas. In China 60% of households have AC while in South Korea this figure jumps to 86%.

According to the IEA AC units see faster growth than any other household appliance over the period to 2040, and become the largest single driver of energy demand growth in buildings. Growth in AC demand tends to follow an ‘S-curve’ in which households tend to begin to want AC installed when income reaches $10,000 per annum and then reaches saturation levels when incomes approach $100,000 per annum (see A chilling prospect).

Tales of King Coal’s death have been greatly exaggerated

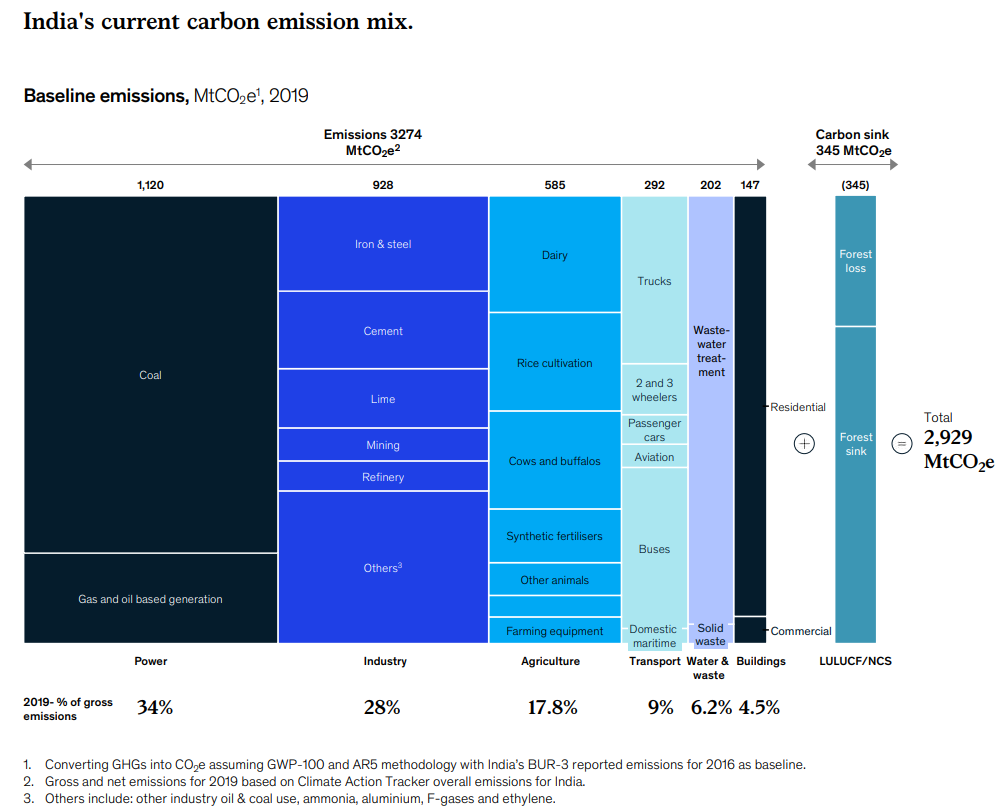

The Indian economy emitted 3.3 Gt of CO2e in 2019. One-third of these emissions come from the power generation sector (primarily coal). In addition, an estimated 28% arises from industrial activities (steel and cement in particular), while 18% come from agriculture (dairy is the largest contributor). Taking account of the country’s natural carbon sinks (estimated to be 0.35 Gt CO2e), India was a net emitter of almost 3 Gt CO2e in 2019.

Overall, India’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are the third largest globally, but much lower down the leader-board on a per person basis. And that’s a concern, especially given the expected take-off in energy and commodity demand as urbanisation gathers pace, and household adoption of appliances reaches the steepest part of the ‘S-curve’. Given that India is so reliant on thermal coal to generate electricity, a massive expansion in energy requirements based on the current energy generation mix would pose a significant risk to global ambitions to meeting net zero.