Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 4,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow on LinkedIn and Bluesky. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents [Start here].

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 8 mins

“the art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to procure the largest quantity of feathers with the least possible amount of hissing.”

-Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV’s finance minister

It’s easy to forget amid the day to day noise around carbon markets, but at their heart, emissions trading schemes are an important, albeit still a relatively small, source of revenue for governments.

Emission allowances are initially distributed into the market via auctions before they are then traded on the secondary market. The revenues generated from auctions are either used to fund investment in carbon abatement, recycled in some way back to households and businesses, or used for general taxation, or some combination of the above.

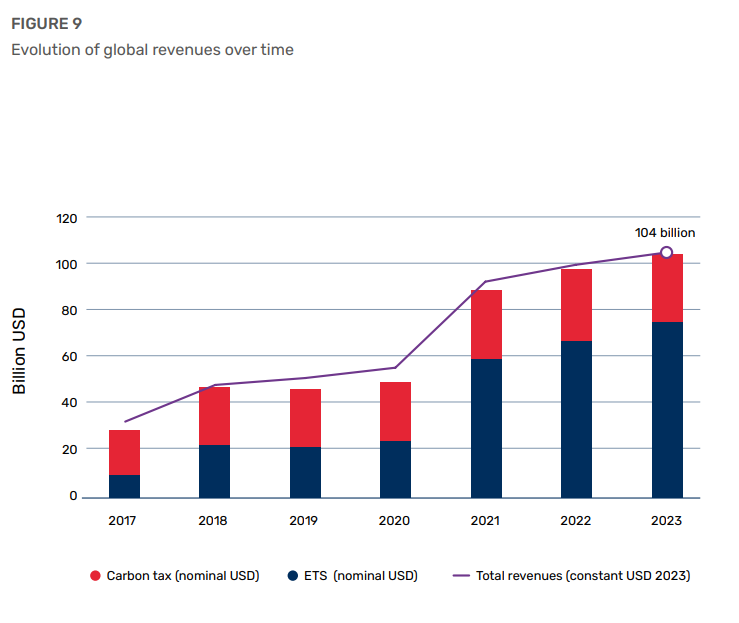

Total carbon pricing revenues exceeded $100 billion for the first time in 2023, according to data compiled by the World Bank. Emission trading schemes (ETS) accounted for over 70% of the revenue generated (of which the EU ETS dominates), supported by the large share of emissions covered by cap-and-trade schemes, and the relatively high carbon prices achieved (see It's the carbon price, stupid!).

Overall, carbon price revenue (including ETS and taxes) is likely to have declined in 2024, as carbon prices typically fell between 2023 and 2024. Any decline is likely to be short-lived however. The phase-out of free allowances in the EU ETS between 2026 and 2034, the inclusion of other sectors of the economy (e.g., maritime), the launch of other ETS’ (e.g., ETS2, Indonesia, Brazil, etc.), and the expansion of other carbon markets (e.g., China’s ETS), looks set to increase global carbon pricing revenues.

Carbon pricing is an alternative source of tax revenue, one that is especially attractive for governments with yawning budget deficits. Once reliable sources of tax revenue - fuel excise and tobacco duties - are in decline as motorists shift to electric vehicles and people give up smoking. Taxing gambling and marijuana (where they are legal) are new sin taxes that have helped plug the gap. The launch of the EU’s CBAM is likely to focus many governments attention (as it has for Indonesia and Brazil, among others), on the potential tax revenue foregone to Brussel’s coffers if they don’t start pricing carbon.

Finally, while Donald Trump’s return to the White House is widely expected to have a negative impact on climate policy ambition at a macro level, it could have a positive knock-on impacts on individual US states. It will be incumbent upon those states considered to be ‘Climate Leaders’ and for which there is positive climate policy momentum, to step up and deliver an ambitious climate policies that can also generate revenue. Carbon pricing, and more specifically so-called “Cap-and-Invest” programs, fit the bill (see What's in a [carbon market] name? Why governments should adopt the 'Cap-and-Invest' nomenclature).1

Government directed carbon prices

Although an ETS should involve setting an emissions cap and then just letting the market decide the price, the reality is that governments and other institutions have several levers by which they can, and often do use, to influence the carbon price.

These include formal mechanised processes such as auction floor and ceiling prices and price containment trigger levels. It also includes informal, ad-hoc market interference involving policymakers commenting on ‘politically acceptable’ price levels or front-loading future auction supplies.

Either way, the idea of the right carbon price - ‘not too hot, not too cold’ - is never too far removed from the minds of politicians worried whether they will still be in office after the next election.