Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below. By subscribing you’ll join more than 5,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out the Carbon Risk backstory and find out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow on LinkedIn, Bluesky, and Notes. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents [Start here].

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 11 mins

“Climate change is the tragedy of the horizon. It’s catastrophic impacts will be felt beyond the traditional horizons of most actors - imposing a cost on future generations that the current generation has no direct incentive to fix. That means beyond the business cycle, the political cycle and potentially the horizons of technocratic authorities, like central banks, which are bound by their mandates.”

- Mark Carney.

The term ‘Tragedy of the Horizon’ was coined by Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, and was first outlined in a speech to the insurance market Lloyds of London in September 2015 when he was the Governor of the Bank of England.1

In his speech, Carney warns that once climate change becomes a defining issue for financial stability it may already be too late to do anything about it. He outlines three broad channels through which climate change is likely to affect financial stability, and while the speed at which such re-pricing occurs is uncertain, it will ultimately be decisive for financial stability:2

“First, physical risks: the impacts today on insurance liabilities and the value of financial assets that arise from climate- and weather-related events, such as floods and storms that damage property or disrupt trade;

Second, liability risks: the impacts that could arise tomorrow if parties who have suffered loss or damage from the effects of climate change seek compensation from those they hold responsible. Such claims could come decades in the future, but have the potential to hit carbon extractors and emitters – and, if they have liability cover, their insurers – the hardest;

Finally, transition risks: the financial risks which could result from the process of adjustment towards a lower-carbon economy. Changes in policy, technology and physical risks could prompt a reassessment of the value of a large range of assets as costs and opportunities become apparent.”

Carney suggests that only through better information, specifically climate disclosures that detail factors such as corporate carbon footprints and how management intends to manage climate related risks, will the Tragedy of the Horizon ultimately be broken:

“With better information as a foundation, we can build a virtuous circle of better understanding of tomorrow’s risks, better pricing for investors, better decisions by policymakers, and a smoother transition to a lower-carbon economy.

By managing what gets measured, we can break the Tragedy of the Horizon.”

Carney’s speech to Lloyds of London in 2015 was well received by the audience. The insurance industry was always going to be the canary in the coalmine when it came to managing the physical risk arising from climate change. Fast forward to early 2025 and Munich Re released a report entitled, ‘Climate change is showing its claws’.

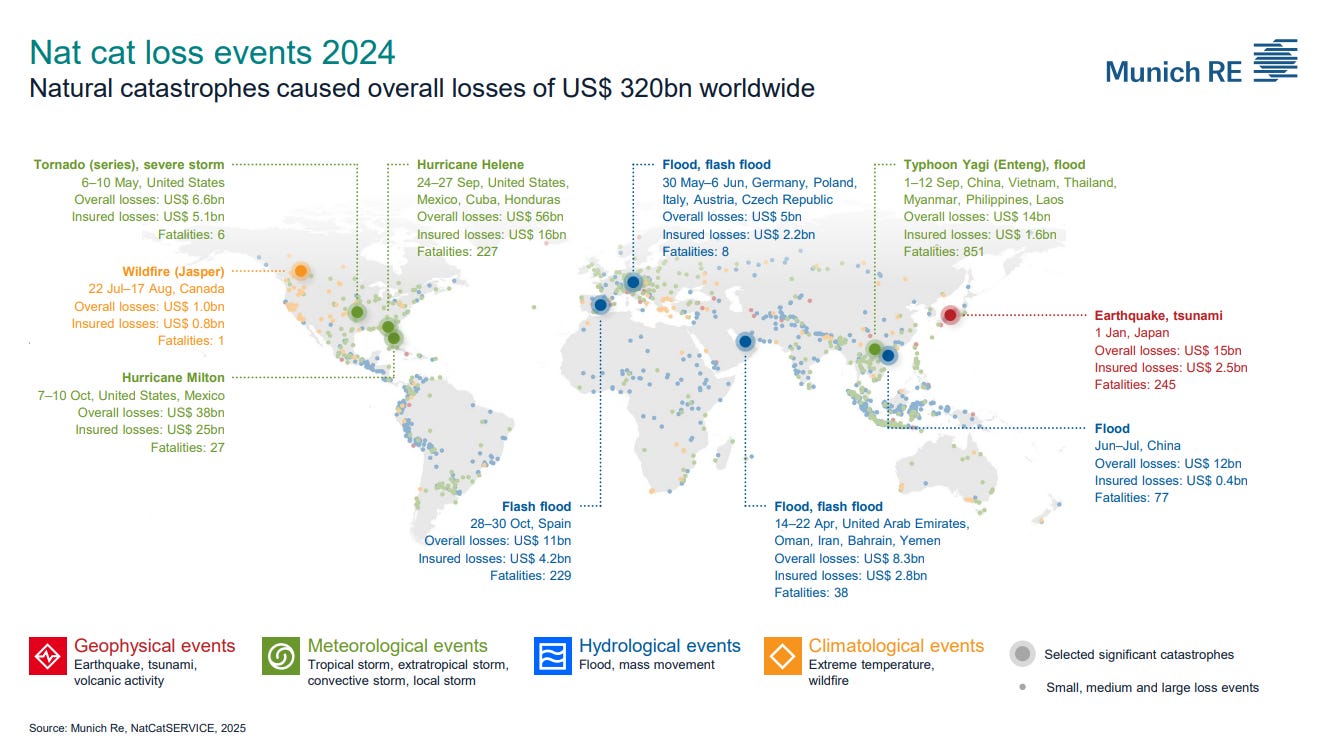

Their analysis revealed that worldwide natural disasters caused losses of $320bn in 2024 (of which around $140bn were insured), considerably higher than the inflation-adjusted average observed over the past 10 years ($236bn). Losses from floods, wildfires, and severe thunderstorms accounted for $136bn of overall global losses in 2024, again well above the 10 year average ($110bn).3

In response, insurers are pulling back from offering cover to homeowners in areas deemed to be at high risk of climate related disasters. Even where insurance is available, homeowners are being forced to pay significantly higher premiums to cover the increased risk of being affected by extreme weather.

Liability risk is also beginning to become more acute, as governments in particular take the lead on pursuing climate compensation. For example, last week a German court rejected a lawsuit brought against RWE by a Peruvian farmer. The farmer alleged that the German utility’s emissions had contributed to higher temperatures, causing the snow caps of the local mountain range to melt, resulting in the farmland below to flood. The case was rejected but the court confirmed for the first time that major emitters can be held liable under German civil law for risks resulting from climate change.

Other jurisdictions are seeking to hold fossil fuel companies accountable for their historical emissions. In the US, lawmakers in New York State passed the Climate Change Superfund Act in late December. It will require companies responsible for the bulk of historic greenhouse gas emissions to pay a combined $3 bn each year for 25 years. The proceeds will then be invested in infrastructure that helps New York recover from and adapt to climate change. The state of Vermont passed a similar law in 2023.

Meanwhile, the European Union has introduced an obligation on fossil fuels firms to establish geological storage sites for CO2 sequestration. The Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA) aims to achieve a CO2 injection capacity of at least 50 Mt CO2 by 2030. In late May lawmakers announced that 44 oil and gas companies such as OMV Petrom and Eni will be required to contribute; their share will be equivalent to the individual company’s EU oil and gas production during the period 2020 to 2023.4

Finally, some forward thinking investors are beginning to price up the physical, liability, and transition risks associated with the Tragedy of the Horizon. Norway’s $1.8 trillion sovereign wealth fund, Norges Bank Investment Management (NBIM), has broken new ground for climate, nature, and biodiversity reporting — remember how Carney said that information would be the key to breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon.

In late February the fund published a report entitled ‘Climate and nature disclosures 2024’ outlining how their portfolio interacts with critical environmental risk factors, what they are measuring to quantify these factors across the globe, and how they are repositioning their portfolio to benefit from a repricing of climate risk.5

The report highlights how NBIM use multiple data sources and techniques to analyse climate and nature risks and opportunities. These include relying on AI to extract tailored climate disclosure data directly from corporate reporting, using geospatial analysis to understand their portfolio’s impacts and dependencies on ecosystem services, and finally, developed a tool that quantifies the cost to society as a result of companies direct impact on the environment (see Down to earth: Putting a value on biodiversity has consequences, and not all good).

Last year NBIM started to develop a top-down approach to stress test their equity portfolio against an extreme physical climate risk scenario. The modelling estimated the present value of average expected losses from physical climate risk on their US equity investments was 19%, compared to 2% with the MSCI’s bottom-up approach. As the footnote to the table below shows, systemic impacts or parallel economic shocks that could result from negative feedback loops are not included in the estimate of climate risk, so their analysis probably underestimates the downside risks.

It’s worth noting that NBIM is a sovereign wealth fund and doesn’t operate in the same way as other large investment funds. Ultimately it’s beholden to the Norwegian government and the Norwegian citizens.

NBIM’s management mandate is set by the Norwegian Ministry of Finance and states that its activities shall be “based on the long-term goal that the companies in the investment portfolio organise their activities in such a way as to make these compatible with global net zero emissions in accordance with the Paris Agreement.”

The fund does own approximately 1.5% of all shares in the worlds listed companies, making it the largest single owner. With that NBIM are in a position to pressure other investors to follow its lead, and set the standard by which companies within its portfolio will be judged.

What then of the supposed guardians of the financial system: the central banks? Many economic commentators, most notably former US Treasury Secretary, Larry Summers have criticised central bankers who stray too far from their day jobs and opine on issues including climate change. In 2020, in an interview with Bloomberg, Summers issued this rebuke to central bankers: “They do not have the capacity to fight climate change. They need to acknowledge the limitations of their influence.”

There is some evidence that certain central banks have retreated from taking a lead on climate change risk. Mark Carney’s previous employer, the Bank of England (BoE), appears to have downgraded climate change as a risk to financial stability since he left the post. In a recent article in the Financial Times, several people who left the Bank since 2020 report that climate change has been deprioritised under Andrew Bailey, Carney’s successor as Governor:6

“A senior official said it was now “in the middle of the pack”, with the European Central Bank “in the lead” and the US Federal Reserve “behind”. But the former employees said they feared the change in priorities had caused the BoE’s technical risk-modelling capacity to fall behind that of the private sector, even as the effects of climate change on the UK have intensified.”

Nevertheless, fears that the Bank might be neglecting Carney’s climate risk legacy entirely appear to be wide of the mark. In late April, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), the UK's financial regulatory body and part of the BoE, published a new consultation paper proposing a change in climate risk governance for the UK financial system. In addition to proposals for greater governance accountability, regular scenario analysis and stress testing, the PRA also calls for tighter data quality and disclosure standards.7

Furthermore, central banks are being encouraged to think through the consequences of near-term climate risks. The Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) has just released its first short-term climate scenarios covering the period 2025 to 2030. The aim of the report is to help central banks analyse the potential near-term impacts of climate policies and climate change on financial stability and economic resilience.8

The contribution by the NGFS is a step forward, bringing the Tragedy of the Horizon fully into view of central bankers. However, as Mark Cliffe, former Chief Economist of ING Group outlines in a recent article, although there’s much to be applauded in the report, the simulations bear little resemblance to the real world, and that’s a problem if climate risk is going to be correctly priced:9

The ongoing failure to consider realistic narratives means that their models are not being asked the right questions. By ignoring crucial risks and interactions, these scenarios barely scratch the surface of the potential range of possibilities we face over the next few years.

The new set of four short-term scenario narratives suffer from two essential problems. The first is that they treat physical and transition risks as strangely separable. Only one of the four scenarios involves both physical and transition risk while the remaining scenarios only examine one or the other, despite the near-inevitability that both types of risk will increase over the next five years.

Where does that leave us? The Tragedy of the Horizon has meant that we have been systematically undervaluing climate risks, leaving a tragic legacy for future generations. Despite some missteps, there is also reason for optimism. Markets are beginning to sniff out both the risks and the opportunities that climate change represents. I will leave the final word to an extract from Mark Carney’s book, Values: An Economists Guide to Everything That Matters:

“A market in transition to 1.5 C is being built. It will reveal how the valuations of companies will change as climate policies adapt and carbon intensity declines. It will allow feedback between the market and policymaking, with policymakers learning from markets’ reactions, and markets internalising policymakers objectives, strategies and instruments. It will expose the likely future cost of doing business, of paying for emissions and of tighter regulation. It will help smooth price adjustments as opinions change, rather than concentrating them in a climate Minsky moment. And it will open up the greatest commercial opportunity of our time.”

👋 If you have your own newsletter on Substack and enjoy my writing, please consider recommending Carbon Risk to help grow this amazing community of readers! Thank You!👍

Climate change - A tragedy in three parts

Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full acce…

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2015/breaking-the-tragedy-of-the-horizon-climate-change-and-financial-stability

A 2024 independent study conducted by European universities found that financial institutions could be underestimating investor losses from physical climate risk by as much as 70% https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-024-48820-1

https://www.munichre.com/en/company/media-relations/media-information-and-corporate-news/media-information/2025/natural-disaster-figures-2024.html#-1537950557

https://climate.ec.europa.eu/news-your-voice/news/commission-identifies-eu-oil-and-gas-producers-provide-new-co2-storage-solutions-hard-abate-2025-05-22_en

https://www.nbim.no/contentassets/6fdfd333e6bf460f8e538b9b55a95bb7/gpfg-climate-and-nature-disclosures-2024.pdf

https://www.ngfs.net/en/publications-and-statistics/publications/ngfs-short-term-climate-scenarios-central-banks-and-supervisors

https://www.ft.com/content/c9919c02-8328-4fa0-af4d-a108770a9f73

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/prudential-regulation/publication/2025/april/enhancing-banks-and-insurers-approaches-to-managing-climate-related-risks-consultation-paper

https://markcliffe.wordpress.com/