The carbon tracking opportunity

Real time tracking of GHG emissions and carbon sinks is a huge growth market

As governments, corporates and financial institutions begin to realise they may be sitting on a big uncovered short position on carbon, demand for data and analytics that helps them begin to manage that carbon risk, and take advantage of any opportunities is growing fast.

Global investment into climate change data intelligence start-ups has surged over the past couple of years. Over $2.8 billion in capital was raised during the first three quarters of 2022, according to PwC' analysis, up five-fold on levels seen during the period 2018-2020.

There are three main investment trends that venture capitalists and other investors are leveraging to gather better climate insights - monitoring and quantifying emissions, mapping and measuring carbon sinks, and company-level measurement and reporting:

Monitoring and quantifying emissions: Regulated emissions trading schemes such as the EU ETS rely on verified emissions by third parties. Remote monitoring of emissions is becoming more important for financial markets. As greenhouse gas levies get rolled out to specific sectors, remote tracking technology will provide an early sign as to whether obligated entities are complying with the regulations.

Mapping and measuring carbon sinks: Nature-based carbon sinks including forests, soil and mangroves will become increasingly important to meeting net zero. As their value rises so the greater the incentive to protect and accurately monitor the region for changes in land use.

Company-level measurement and reporting: More onerous climate reporting requirements mean that there is greater demand from companies wanting to track and measure their carbon footprints, and assess the climate risk associated with their future investments.

Each of these investment trends is interrelated, and is likely to become ever more so as carbon markets become more globalised, multi-national companies start to map their entire Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions, and global treaties on a range of greenhouse gases and pollutants become more stringent. This article delves a bit more deeply into each of the three key investment themes, piecing together the main demand drivers underpinning the investment case, and outlines where I think things may develop over the next few years.

Carbon checking

In the past, commodity producers and trading houses would deploy people to count cocoa stocks in the Ivory Coast, use infrared cameras to monitor oil levels in storage tanks in the US, count crude and product tankers discharging at ports, or set up cameras to film coal stocks at Japanese power stations. The firms used this data to determine inventory levels and profit from price discrepancies. Although some of these methods are still being used, satellites and drones, combined with on the ground verification are increasingly being used to monitor fundamentals in ‘real time’.

These same technologies have been deployed to monitor emissions from power stations, factories and airplanes. Remember that the EU ETS reached a €750 billion market valuation in 2022, with other compliance markets accounting for an additional €100 billion. Meanwhile, the value of individual companies is being increasingly affected by their exposure to compliance carbon markets. Gaining advanced insight into the potential demand for EUAs is very valuable for carbon focused investment funds, large compliance entities and investors in Europe’s equity markets (see Does the stock market care about the carbon price?).1

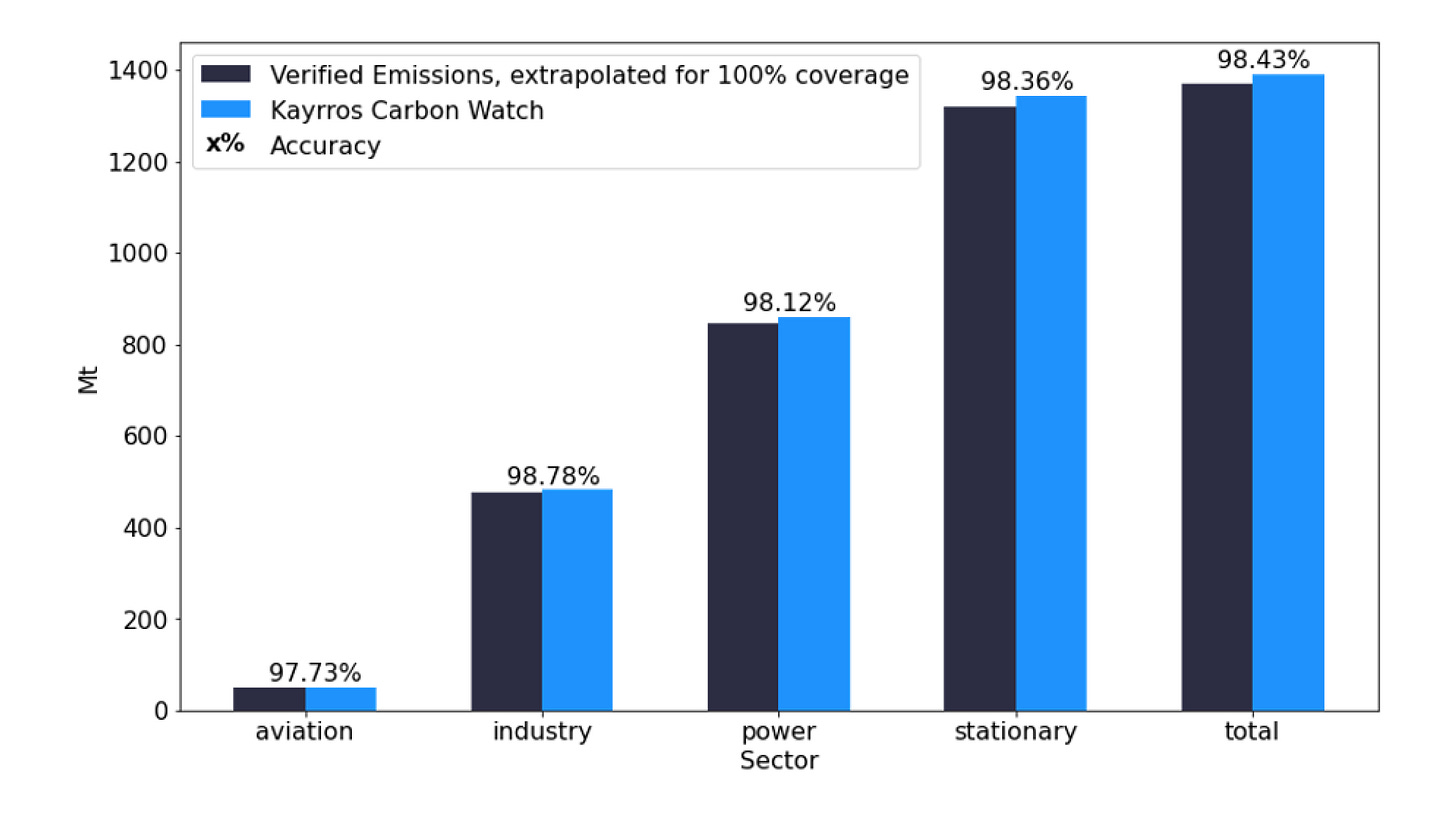

The chart below shows 2022 EU ETS emissions by sector, comparing verified emissions data and estimates made by Kayrros, a French geo-analytics company, using satellite technology. Overall, Kayrros’ estimates of EU ETS emissions achieved a 98.43% accuracy, with industrial emissions 98.78% accurate. This might explain why the publication of EU ETS verified emissions, at the beginning of April each year, is not the market moving data release it once was (see The only number that matters).2

EU ETS verified emissions, 2022

It’s not only those emissions trading schemes that correspond to a certain jurisdiction that are likely to face increased calls for emissions monitoring. On a global basis, as the focus shifts to cutting carbon emissions, countries greenhouse gas data will face much greater scrutiny, especially once global carbon trading occurs under Article 6. As I outline in How much should we trust the dictator’s CO2 estimates?, governments have every incentive to exaggerate how well their economy is doing, and they tend to do this in more authoritarian countries. Could the same incentive to lie exist when discussing the quality of a country’s air?

Last November, the Climate TRACE coalition released the most detailed facility-level global inventory of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to date, including emissions data for 72,612 individual sources worldwide. It revealed that emissions from top oil and gas-producing countries, which report their data to the UN, are up to three times higher than self-reported figures, in part, due to insufficient reporting requirements and consistent underestimation of methane emissions from both intentional flaring and leaks.3

Methane “super-emitters”

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) introduces a fee on methane emitted by US oil and gas companies. The methane emissions charge as its known begins in 2024 at $900 ($36 per tonne of CO2e), increases to $1,200 ($48 per tonne of CO2e) in 2025, and will rise to $1,500 a tonne ($60 per tonne of CO2e) in 2026 (see Pricing methane emissions out of the atmosphere). The methane charge is likely to accelerate the market for monitoring systems that can detect and track methane emissions.

The US oil and gas methane detection market could be worth $533 million by 2025, according to projections from BNEF versus a global market of $918 million. One third of this investment is expected to go into satellite monitoring, 35%-40% into drone and aircraft monitoring, with the remainder spent on sensors. As Kayrros outline in this report with the International Energy Forum, a combination of these technologies - including AI - are required to accurately estimate emissions, and this is being refined constantly.

BNEF estimate that the total global addressable market for methane detection from the oil and gas industry could be in the region of $14.9 billion. However, to achieve that market valuation, methane emissions outside of the US and Europe will need to receive significantly more regulatory attention. As monitoring technology develops there is no reason that regulations including levies could not be imposed on other sectors of the economy responsible for significant methane emissions. In turn that will increase the potential size of the global methane emission detection market.4

For example, technology is being used to identify the worst culprits responsible for huge plumes of methane emissions. Satellite data analysed by Kayrros identified 1,005 super-emitter events in 2022. These “super-emitters” as they are known, are estimated to contribute up to half of total methane emissions for some countries, with around 100 of these major methane leaks happening in the world at any one time. Although some may only last a few hours, some may splurge methane for several months. Over half (559) were identified as oil and gas fields in 2022, 105 were coalmines, and 340 of the “super-emitters” were waste sites. At 184, Turkmenistan had the highest number of super-emitting events - a function of aging Soviet infrastructure. It also had the biggest leak - 427 tonnes an hour - in August, near a major pipeline.

As regular readers of Carbon Risk will know, man-made emissions of methane are not the sole fault of the fossil fuel industry. The worlds largest meat and dairy corporations are under pressure to cut greenhouse gas emissions too. Some 15% of total GHG emissions (81 Gt CO2e) rise as a result of animal related products, with half of this estimated to be methane. As these companies increase their commitments under the Global Methane Pledge and increasingly become subject to emissions pricing then the demand for remote emissions monitoring will grow (see Better in than out: The worlds largest meat and dairy corporations are under pressure to cut greenhouse gas emissions).

Deforestation’s minority report

In Protection money I discuss the challenges involved with protecting vulnerable parts of tropical rainforests from environmentally damaging economic development; things like illegal logging, cattle grazing and mining. One option is to compensate landowners for the opportunity cost associated with the value of commodities that could be extracted from deforested land. Protecting the frontier of the forest means that the economics of exploiting the interior become much more difficult to stack up. However, as I outline in the article, the cost involved with persuading landowners and other agents not to deforest is immense.

An alternative approach that can help enforcement of existing deforestation laws is being developed by environmental non-profit organisation Imazon. They have developed an artificial intelligence platform designed to prevent deforestation from happening at all, by first predicting the areas where it is most likely to occur.

According to Imazon, 90% of accumulated deforestation is concentrated within 5.5km of a road, 90% of logging takes place within 3km, and 85% of fires within 5km. That means monitoring the construction of roads is crucial to predicting where deforestation is likely to occur next. PrevisIA combs through thousands of satellite images to spot new roads slicing through the biome, notifying agencies that monitor the forest of the high-risk areas, enabling enforcement agencies to warn landowners of the penalties, should deforestation occur.5

Everything including the carbon sink

Nature-based carbon credits, in particular those associated with REDD+, have come in for significant criticism over the past six months. Although some of the negativity has been warranted, much of it belies a false belief in how the projects work in the real world. Simply because they have passed all the verification checks does not mean that the carbon project has a 100% chance of success. Their success or failure in avoiding emissions or removing carbon from the atmosphere is subject to significant uncertainty, as is any venture.

Carbon credit ratings agencies such as BeZero and Sylvera use a combination of observation techniques, from satellites to ground-level measurement, coupled with advances in AI to assess the quality of nature-based projects. The technology can be used detect ecosystem change with greater accuracy, distinguish observed change from business as usual, using dynamic baselines, and systematically refine assessments of carbon stock densities.

Specifically the firms have invested in the technology to help them assess the risk of additionality, over-crediting, non-permanence and leakage. The idea is to get to a situation where the rating represents the risk that the carbon offset project fails to deliver its claims. For example, ‘D’ rated projects will be cheap, but they come with high risk of ‘greenwash’. ‘AAA’ rated projects will be expensive, but they reflect the low risks involved to the buyer. At least then, buyers can make an informed decision about how they use carbon credits to help them meet their net zero strategy.

Although people tend to think about forests when they first consider the role of natural carbon sinks to mitigate climate change, they tend to forget what lies beneath may be even more important. Minor changes in that vast carbon sink beneath us have major implications for the amount of carbon in the atmosphere and the outlook for global warming. Some estimates suggest that soil degradation due to human activity has contributed about a quarter of all manmade global greenhouse gas emissions. Soil also has the potential to act as a big carbon sink, if we manage it effectively. Recent estimates suggest that global soil carbon sequestration has the potential to be in the range of 2-6 GtCO2 each year, assuming full adoption of carbon sequestration practices.

As I outline in Carbon farming puts a value on dirt, one of the main types of companies to benefit from the influx of capital from venture capitalists over the past 18 months are start-ups specialising in climate change data intelligence, many of which are focusing on soil. Rather than relying on the lengthy and costly process involved with physical soil sampling, soil data firms are making use of satellites, drones, machine learning, coupled with ground observation to track soil quality in real time. For now at least, attention is focused on the US and Australia, both countries with large farms and a burgeoning soil carbon credit market. As the technology improves there is scope for other markets that value the soils carbon sink properties correctly to emerge.

Corporate carbon accountancy

Individual companies may have to report on their Scope 1 carbon emissions if they are obligated under a emissions trading scheme. Some, such as those oil and gas companies subject to the methane charge in the US, will soon be required to report on their methane emissions, while others may be doing it voluntarily under The Methane Pledge.

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the US government agency responsible for ensuring the integrity of securities markets, is expected to publish new rules shortly requiring listed companies to provide detailed climate related disclosures. This includes vital quantitative data such as greenhouse gas emissions - Scope 1, Scope 2 and Scope 3 (the latter only where they were deemed “material or if the registrant has set a GHG emissions target or goal that includes Scope 3 emissions”.6

In Owning up to Scope 3, I argue that, “there is going to be increased demand for services that can monitor emissions in real time, for example companies that use drones, satellites, AI, etc to accurately report and benchmark different GHG emissions. All of this data will require software that can source and collate disparate data sources together. Demand for trusted carbon accountants will also increase.”

For those companies that have to, or decide to report their Scope 3 emissions there is going to be increased demand for data that can prove the provenance of a particular commodity or good. It is increasingly being pursued to track deforestation risks, but will need to be a lot more comprehensive if we are to accurately track Scope 3 emissions, both up and down the supply chain for various industries.

The material damage to a company that fails to accurately report on emissions could be high. For example, accusations of cheating or greenwashing, overall bad publicity, losing their ability to borrow on competitive terms. It’s possible that investors will use satellite and other remote monitoring to track the emissions of companies (and indeed whole countries) required to publish their emissions. Maybe even competitors in the same industry will use the technology to keep tabs on each other (see Not just hot air?).

A 'green' unicorn

“It is my belief that the next 1,000 unicorns — companies that have a market valuation over a billion dollars — won’t be a search engine, won’t be a media company, they’ll be businesses developing green hydrogen, green agriculture, green steel and green cement,” - Larry Fink, CEO and Chairman of Blackrock, 25th October 2021

https://twitter.com/Kayrros/status/1647876135814930432/photo/1

https://www.reuters.com/business/sustainable-business/global-carbon-markets-value-hit-record-909-bln-last-year-2023-02-07/#:~:text=The%20world's%20biggest%20carbon%20market,87%25%20of%20the%20global%20total.

https://climatetrace.org/news/more-than-70000-of-the-highest-emitting-greenhouse-gas

Satellite data analysed by Kayrros identified 1,005 super-emitter events in 2022. These “super-emitters” as they are known, are estimated to contribute up to half of total methane emissions for some countries, with around 100 of these major methane leaks happening in the world at any one time. Although some may only last a few hours, some may splurge methane for several months. Over half (559) were identified as oil and gas fields in 2022, 105 were coalmines, and 340 of the “super-emitters” were waste sites. At 184, Turkmenistan had the highest number of super-emitting events - a function of aging Soviet infrastructure. It also had the biggest leak - 427 tonnes an hour - in August, near a major pipeline.

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2023/apr/29/could-ai-save-amazon-rainforest-artificial-intelligence-conservation-deforestation

According to the SEC proposal, published in March 2022, large companies would be required to disclose and have independently verified their Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. Unlike Scope 1 and 2 emissions, Scope 3 emission disclosures would not need third-party verification and would be protected from legal liabilities.