In 2021, world leaders from countries that contain close to 85% of the world’s forests agreed to end net deforestation by 2030. Halting deforestation is critical to meeting the 2050 net zero targets because when forests are cut down, vast quantities of carbon are released, while the carbon sequestration potential is lost.

There is no pathway to limit global warming to 1.5°C without immediate action to halt deforestation. However, to be on course for 2030, deforestation rates needs to decline by 10% per year, every year.

Unfortunately, the value we currently place on tropical forests in particular, is far too low if we want to protect them from deforestation.

A recent report by the Energy Transitions Commission (ETC) suggests that payments to protect the frontier of tropical forests from being cleared and releasing carbon into the atmosphere, will need to rise by at least 50-fold per year compared with current funding arrangements. However, once you take full account of the opportunity cost of the land to those who would look to exploit it for commodities and other uses, payments will need to rise at least 400-fold per year.1

Commodities are the primary driver of deforestation in the tropical rainforests of Latin America and South East Asia. It typically involves the permanent conversion of forests to graze cattle or to grow oilseeds such as soy and palm oil. In contrast, shifting agriculture is the main cause of deforestation in West African tropical forests. This latter process involves the clearing of forest for agriculture, often by smallholder farming, before it is then temporarily abandoned.

Although some governments have succeeded in implementing measures protecting vulnerable parts of their tropical forest from economic development, via effective monitoring and enforcement of anti-deforestation laws, for the most part this has only been achieved to a very limited degree.

In the absence of adequate protection by the state, another way to deal with deforestation is to tackle the underlying incentives, enabling landowners and other agents to put a value on the forest and the embedded carbon. This means they can then make an informed decision as to the economic value of cutting down the forest to grow crops and graze cattle, versus the value of maintaining the forests in-situ.

The opportunity cost of not deforesting will vary significantly depending on the attractiveness of the local soil and climatic conditions, the input and supply chain costs required to extract the commodities and access to the end market (e.g. labour, transport, storage, regulatory enforcement), and finally, the type of commodities produced and the price they can be sold at.

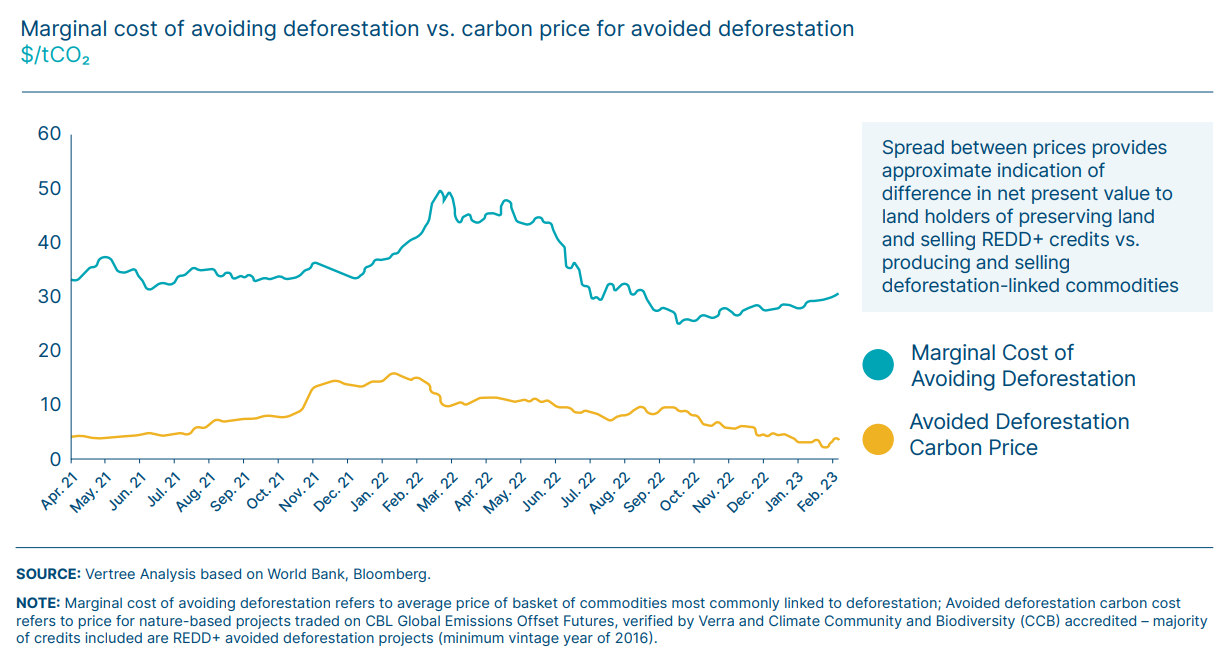

The marginal cost of avoiding deforestation is ~$35 per tonne of CO2, according to estimates by Vertree. Their analysis is based on the cost of producing and selling deforestation linked commodities in over 50 tropical forest countries, including Brazil, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo. This tallies with other research published in 2019 that calculated the average opportunity cost of avoided oil palm expansion in Indonesia at $27.74 per tonne of CO2 (see Nature-based carbon credit prices need to rise: High commodity prices increase the incentive to clear forests and plant crops).

Compensation to landowners to avoid deforestation is significantly less than $5 per tonne CO2 based on the Nature-Based Global Emissions Offset (N-GEO) futures contract price. Meanwhile, price assessments by Trove Research analysing both exchange and OTC trades suggest the weighted average REDD+ price was around $8 per tonne CO2 in late Q1 2023, down from $14 per tonne CO2 in early 2022.

Whichever way you price it, the economic case for deforestation is well in the money.

In theory at least, if the carbon price equals the marginal cost of avoiding deforestation then the landowner would be indifferent between deforesting to produce commodities, and keeping the forest standing and generating carbon credit payments. However, merely being indifferent to cutting down the forest or not is unlikely to be a sufficient condition to persuade farmers and ranchers to refrain from doing so.