Not just hot air?

Carbon and climate change has become a big talking point during quarterly earnings calls.

The calls are usually hosted by a publicly traded company after the publication of its earnings reports for a given period (typically quarterly). Investors, equity analysts, and business journalists listen in or comb the transcripts of the call for clues as to the company’s future prospects. Importantly, earnings calls also offer a way for company executives to massage how they would like investors to perceive the company’s stock.

Climate related talk in earnings calls was fairly constant during the first 18 years of the 21st Century. It rose gradually between 2002 and 2008/09, and then as the Great Financial Crisis hit and global efforts to accelerate climate policy stumbled, talk of carbon and other climate related discussions took a back seat.

By 2018, discussions about climate change had withered back to levels last seen in 2002. Even the Paris Agreement of 2015, the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the launch of initiatives such as Science Based Targets were not enough to spark a change in conversation from corporate executives. Indeed, it wasn’t until 2019 that executives began to reflect these developments in their discussions with investors. Over the next three years global climate related discussions in earnings calls soared by two-thirds.1

What caused the spike in executives opening up about climate change to their investors, the analysts that cover their firm, and the journalists that write stories about them? Talk is cheap, as the saying goes. A cynical mind might even suggest that CEO’s and other execs were only interested in bolstering their stock price in the eyes of ESG orientated investors. The performance of low carbon portfolios only really began to take-off in 2019 after all, with companies seen as being high carbon intensive seeing their share price underperform (see Does the stock market care about the carbon price?).2

It is important that investors can assess the risk that a company will respond to climate policy and the concerns of its stakeholders. For example, it may give an indication of the amount it will need to invest to decarbonise, and the amount of money it will need to find to cover its carbon compliance costs.

Academics from the Swiss Finance Institute and Stockholm’s Business School and School of Economics compared their corporate climate discussion data with company reported emissions to see if there was a connection. They wanted to answer the question: Do firms with more climate talk in earnings calls reduce CO2 emissions by more (or increase them by less) than companies with less climate talk? In short, is climate talk cheap?3

First off it’s important to see which industries typically see their executives talk the most about climate change during earnings calls. The data shows that climate related talk tended to be relatively high if a company is from a sector for which climate change is highly material (e.g. resource intensive and alternative energy industries), if they are being targeted by a climate-focused investor coalition such as Climate Action 100+, or if they have endorsed the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

The researchers did find evidence of a relationship. An increase in climate-related talk tended to be associated with a reduction in CO2 emission (or a smaller increase in emissions) in the years after the earnings call. Importantly though, the researchers discovered that a high degree of climate related terms in the Q&A session (following the boards presentation) was very strongly associated with subsequent reductions in CO2 emissions. Given this part of the earnings call is less scripted, a strong degree of climate related discussion in the Q&A probably gives the best indication that executives mean what they say. Note the use of the word associated. While the analysis may suggest causality between the two metrics, it’s also possible that they are related for other reasons (see Owning up to Scope 3).

Finally, the researchers discovered that across the period 2002 to 2022, climate-related talk was typically negatively associated with the company’s stock price during the earnings announcement period. This may partly explain the reluctance among executives, earlier in the sample period, to talk about climate change issues. Further analysis showed that investors were particularly critical of climate talk by firms based in countries where climate change scepticism is high.

However, as I mentioned earlier, changing attitudes to ESG related investments may indicate that the relationship has disappeared, or at least reduced, in later parts of the sample period. Given that the analysis also ends in Q2 2022 (arguably the peak in ESG related investment), we might expect corporations to have become more circumspect about their use of climate language, especially when it could be accused of being ‘greenwashing’ (see ESG investment backlash hits nature-based carbon credit prices).

What other evidence is there that climate related words count? Academics at Tohoku and Kyoto Universities set out to investigate the sincerity of the four oil & gas majors (BP, ExxonMobil, Chevron and Shell) by analysing language used in their annual reports and comparing it to the reality of their real-world activities and investment portfolios.4

They first examined the frequency by which 39 keywords relating to climate change, transition, emissions and low-carbon energy, appeared in the company’s annual report. Of the four majors, Chevron lagged well behind and has only recently begun to use more frequent climate related terminology in its annual report.

Chart 6: Frequency of climate related words in the annual reports of the big four oil and gas majors

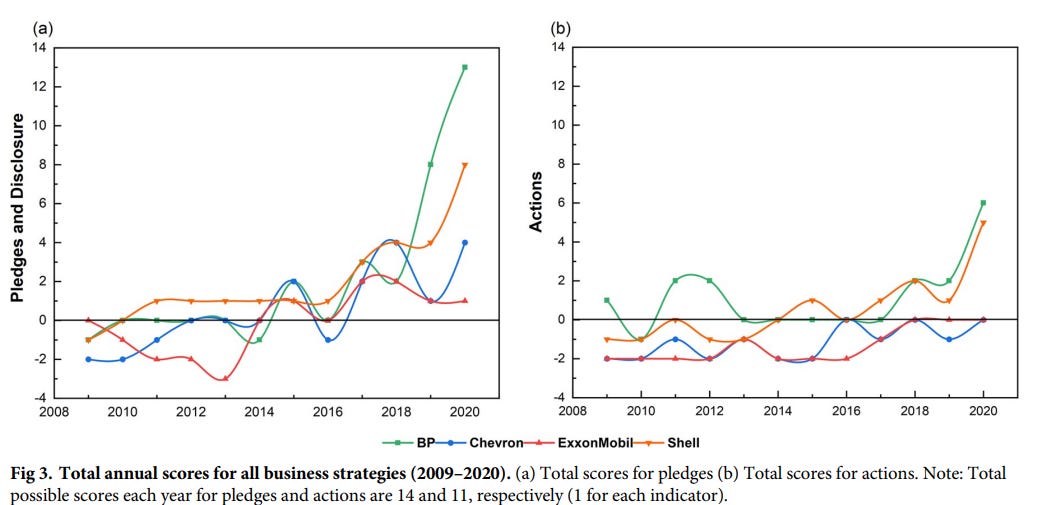

They then ranked each companies annual performance based on the strength of its climate pledges, and the actions it took to meet those pledges. What it reveals is that BP in particular made some bold pledges, however once its actions were assessed they were found to be lacking.

Not to be outdone, the company, whose then chairman coined the moniker “Beyond Petroleum” back in 2000, announced twenty years later that it would become a net zero company by 2050 or sooner, adding that it planned to cut emissions by 35-40% by 2030. In the past week BP announced that it would now look to cut emissions by between 20 and 30% instead (see VCM futures no refuge from equity market malaise: Strong corporate demand for carbon credits masks declining willingness to pay).

My point in picking on BP is not to pick faults with its strategy. The world has underinvested in oil and gas for some time, and we will need it for longer than many expect. No, my argument is that it serves to highlight the risk that investors face if they rely too much on the prepared words of a company CEO, whether those words are printed in an annual report or fall off the lips of a CEO during an earnings call presentation.

Chart 7: Climate change pledges versus actions

If you want to know whether a company is really going to follow through on its words and cut emissions or not, don’t focus on their prepared remarks. Instead, challenge them in the Q&A session of an earnings call. Their words will probably reveal their true preferences.

The data accounts for the quarterly earnings calls of all publicly listed companies worldwide from 2002 until the end of the second quarter of 2022. The sample included around 400,000 earnings calls for more than 11,000 unique companies.

The United States contributes most firms to the sample, around 63% of all firms. Canada, Germany, Japan, and Sweden follow on ranks two through five.

The sample is more populated in the most recent years of the sample period. For example, 2019 contains roughly 14% of all the firm-quarters, whereas 2002 contains just 0.6%. This is due to the growing availability of ESG and conference call transcript data over time.

The researchers captured the extent to which companies discuss climate change in their earnings calls by measuring the textual similarity between the transcripts of such calls and the five assessment reports published by the IPCC at regular intervals between 1992 and 2014.

https://www.ft.com/content/c2937d7b-98f1-4179-823c-4a58e21f8e30

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4021061

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0263596