Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 3,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow my posts on LinkedIn. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents.

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 10 mins

“The electric vehicle revolution is running out of steam” - The FT

“Industry pain abounds as electric car demand hits slowdown” - Reuters

“Tesla can’t outrun the EV slowdown” - Business Insider

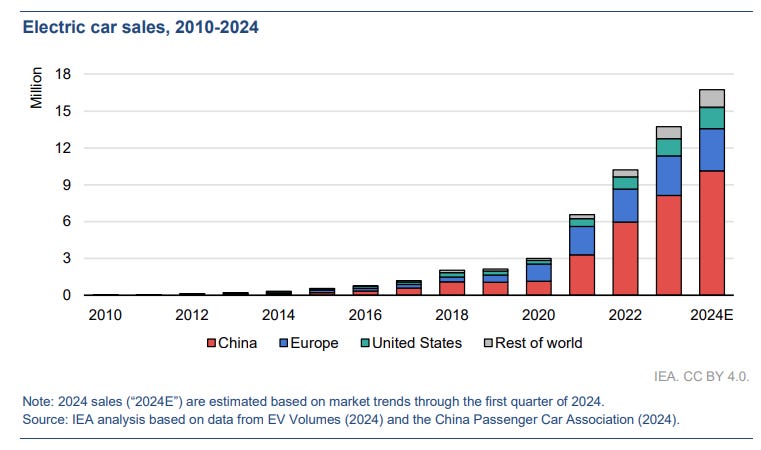

If you took recent headlines in the press at face value you would think that no one is buying electric vehicles anymore. Yet despite recent investor worries about Tesla and BYD sales in Q1 2024, overall global EV sales in the first quarter are actually up 25% versus year earlier according to data published by the International Energy Agency (IEA). China accounted for the majority of that growth, with EV sales up almost 35% year-on-year. Sales in the US rose by 15%, while Europe observed a 5% increase in EV sales. Annualised Q1 2024 sales (typically 15-20% of annual EV sales) suggests that global sales of EVs in 2024 could reach 17 million, which if it materialises, will mean a 20% rise on 2023.1

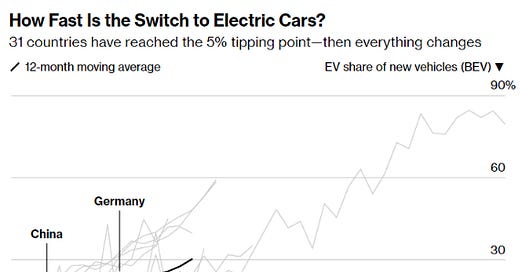

Thirty one countries surpassed a crucial EV tipping point at the end of 2023, whereby new EV car sales surpassed 5% of total new sales. Together these 31 countries account for two-thirds of the worlds car sales. Analysis by Bloomberg Green based on the trajectory taken in countries with higher rates of EV adoption suggests that it only takes 4 years for EV adoption to move from the 5% threshold to 25% of new car sales. Not a single country has taken more than 3 years to go from 5% to 15%. Although Europe remains at the centre of EV adoption (the top 10 countries in terms of EV adoption are all European), some of the fastest growth is happening elsewhere. For example, EV adoption in Thailand only passed the 5% threshold in Q1 2023, but by the end of the year it had already reached 13%. On a global basis, EV adoption reached 12% of new car sales in Q4 2023, having reached 5% in 2021.

The US passed the 5% tipping point towards the end of 2021, and by end 2023 it had reached 8.1% of new sales. That’s far short of the 18.1% average for 20 countries at the same point on the adoption curve, according to Bloomberg Green. In part that’s because American cars tend to be much larger and heavier than those driven in many other countries, in turn requiring much larger batteries; the average car sold in the US in 2022 was 20% heavier than that sold across the Atlantic. It also reflects strategic choices made at the state level regarding policies that support EV rollout; California with EVs ~20% of new car sales, stands out as the exception that proves the rule.

Research into the individuals perceptions of EVs by American consumers by Potential Energy Lab reveals a consensus around high cost and driving range as obstacles to adoption, but a wide disparity of views on pollution and the environment, energy security and EVs importance to US manufacturing. As Bloomberg illustrate in the previous chart, if the US does return to trend it would mean that 25% of new car sales will be EVs by 2026. This seems unlikely. Over a third (37%) of Americans expect to lease or own an EV in the next five years, with 60% expecting to do so in the next 10 years. At the other end of the spectrum, around one-fifth said they would never buy an EV.2

Energy system maximalism

Energy systems derive a significant part of their value from network effects.

The value of oil for example is, at least in part, derived from the transportation and refining network that serves it (the pipelines, tankers, refineries and so on), which in turn enables end consumers to derive value from it. Oil, and for that matter coal or natural gas can be burnt outside of this network, but without access to it the value of the fossil fuels are compromised; the range of applications and the markets for which they can serve are severely diminished.

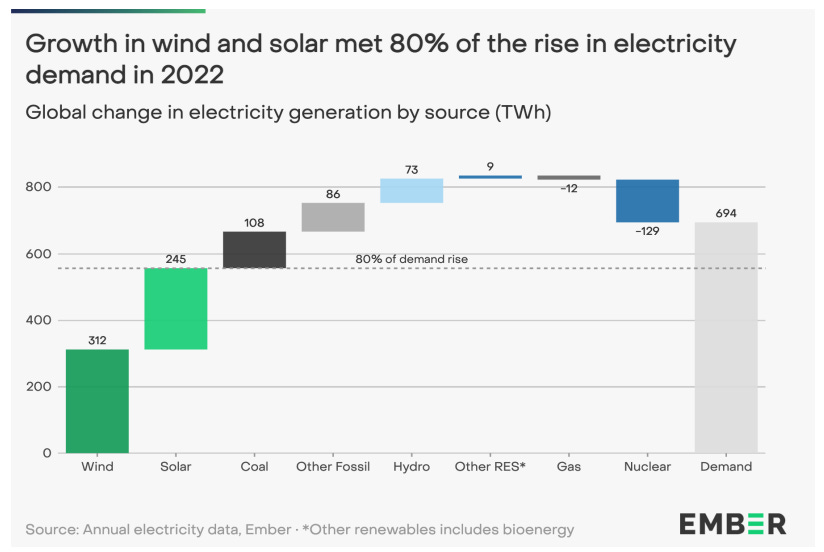

Threats to an incumbent energy system can be profoundly disorientating for people that are physically and financially invested in the network value being maintained. This is why the energy transition - exemplified by the growth in renewables and EVs - is seen as such a threat to the fossil fuel network. Each energy system has their own community of investors and ideological supporters for which there is no alternative - an energy system maximalism where being fully invested (financially and ideologically) in fossil fuels or the green energy transition is seen as the only way forward.

Of course, government policy will play a big part in how this shakes out. Countries have subsidised both fossil fuel supply and demand in the past, and many continue to do so today. At the same time, governments have also employed subsidies to kickstart the growth in renewable energy generation, invested in the rollout of EV charging infrastructure, and offered generous incentives to buy EVs. Ultimately though the future will be determined by the collective choices of millions of individuals, each deciding for themselves which network offers the best value.

It’s worth remembering that all previous energy transitions have been additive in terms of primary energy demand, and so although people may argue about the relative shares, it potentially means that renewable energy, nuclear, and fossil fuels will all have a role to play. Arguably then, nowhere are the battle lines more explicitly drawn than EVs versus internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles.

Perceptions of how EVs will fare in one jurisdiction, perhaps your own country, does not mean that they will suffer the same fate elsewhere in the world. As someone who recently got a Tesla, and immediately sold their diesel car, I have my own limited experience to go on, but equally I know it’s not necessarily representative of others. Path dependency, individual incentives, and local geography matter a great deal.

The EV network effect

The survey by Potential Energy Lab suggests that affordability and range anxiety are the two most important factors holding back EV adoption in the US. Research carried out elsewhere in the world also points the finger at these issues as topping the concerns among drivers. Rather than focus on data in the rear view mirror (i.e., last quarters EV sales), a much better gauge of future EV adoption and the value of the network will be the price of an EV relative to an ICE car, and the growth in the EV charging infrastructure.

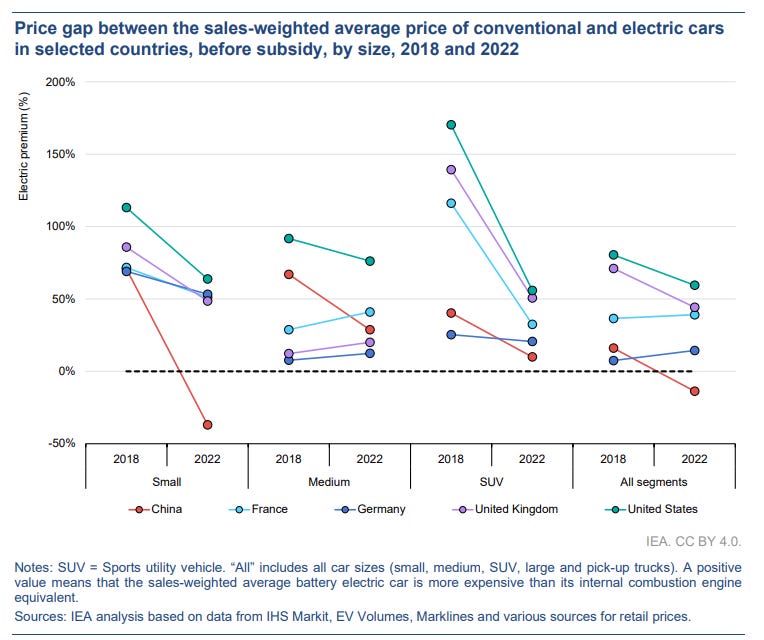

A rapid improvement in affordability is evident in the narrowing of the price gap between EVs and ICE vehicles over the past 5 years; this has occurred across geographies and by model size, by both the retail ticker price and the total cost of ownership (i.e. taking account of lifetime operating costs such as fuel, repairs, etc.). EV manufacture is still on a steep learning curve, while battery prices (the main EV component by value) continues to fall in price (the price of lithium and nickel are down sharply), and see improved performance (longer range models now available). Further cost reductions are likely as economies of scale begin to work through, bringing the cost of an EV more in line, or even below, the cost of an equivalent ICE vehicle.

The decline in the price that EV manufacturers can charge may keep them awake at night, but it’s a good thing for consumers. Tesla’s announcement that it will accelerate the introduction of “more affordable” models, with production expected to start in early 2025, should be seen in this context. Companies selling new products often develop too much capacity early on as management mistakenly believe a short-term upward departure from the exponential growth trajectory will be maintained indefinitely. High levels of competition (there are over 129 EV brands in China for example) may be bad for margins, but it weeds out the bad ideas from the good.

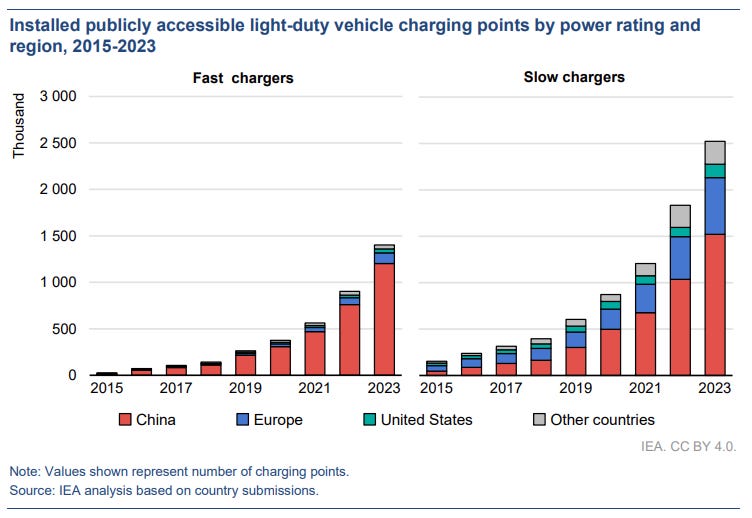

As EV manufacturers increasingly compete on price and gradually begin to bring the cost to the consumer closer to ICE levels, governments are shifting their support towards expanding the EV charging networks. Resolving range anxiety is key to enabling an EV network effect to take hold since demand for EVs depends on the availability of accessible EV charging stations, while the supply of charging infrastructure depends on the installed base of EVs to use the stations. Charging infrastructure includes the ability to power your EV up at home (not always accessible to people, especially in urban areas), and a network of publicly available fast and slow charging stations.

According to the IEA, the global EV charging stock increased by more than 40% in 2023. The number of fast chargers grew by 55%, and now account for 35% of publicly available EV chargers. China dominates the development of slow and fast chargers, and there’s more to come. In their latest report, the IEA note that “China is shifting focus to charging infrastructure development, targeting full coverage in cities and on highways by 2030, as well as expanded rural coverage.” Meanwhile, new EU regulation signed off in late 2023 means that from 2025 onwards there must be a public fast charger every 60km along the EU’s main transport corridors.

Other countries, especially those lower down the adoption curve, are likely to learn the lessons of history, and focus on developing their EV charging networks first. Research carried out by the World Bank found that investing in charging infrastructure is 4-7 times as effective in promoting EV adoption than subsidising the cost of an EV to the consumer. Their analysts calculated that if the $43 billion of subsidies dished out in the top 13 EV markets between 2013 and 2020 had been spent on charging infrastructure instead, it would have resulted in a threefold increase in the cumulative induced EV sales across those 13 end markets.3

EU ETS II and EVs

The future EV adoption trajectory will be of increasing concern for investors in carbon markets too. California has been the pioneer here, but now market participants in other jurisdictions, including Europe as it launches EU ETS II (covering road transportation and heating), will need to factor in EV’s network effects into their strategies. Scheduled to begin trading in 2027, the supply-demand fundamentals underpinning EU ETS II is expected to be incredibly tight, potentially resulting in carbon prices reaching $200 per tonne. The rollout of EV’s and EV charging infrastructure is expected to be the main solution by which this cost can be mitigated.

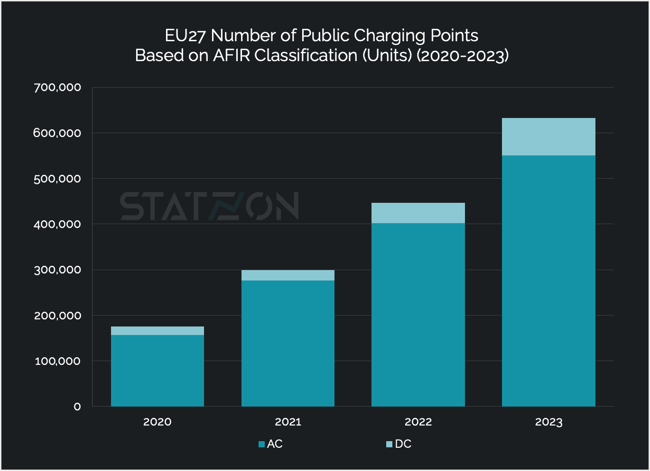

So what does the public EV charging network look like in Europe? The latest data from the European Alternative Fuel Observatory (EAFO) shows that the EU had over 630,000 public charging points by the end of 2023, up from 450,000 a year earlier. Fast chargers make up 7% of the total public charging points, with Norway leading the pack (25% fast chargers), followed by Finland and Estonia (each with 16%), Germany (13%), and Austria (11%).4

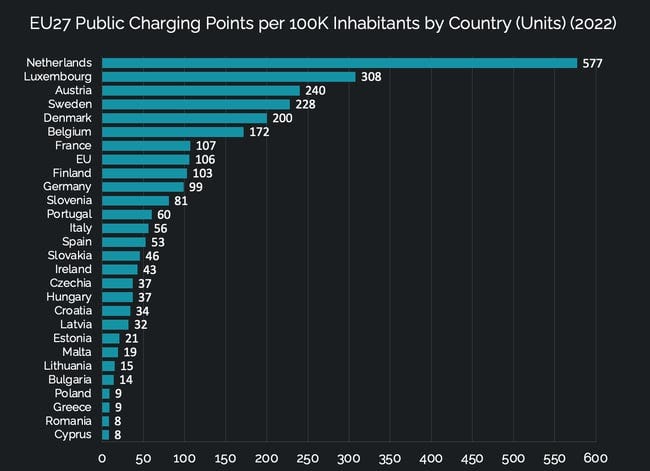

While the growth in overall numbers is encouraging, EV chargers need to be broadly spread geographically, close to population centres, and along transport routes for the EV network value to be maximised. At the moment, Europe’s EV charging network is heavily concentrated. In 2023, over half (52%) of Europe's total charging infrastructure was concentrated in just three countries: the Netherlands, Germany, and France. Netherlands also has by far the most public charging points per head of population.

One of the main obstacle’s to broader EV charging infrastructure coverage is permitting. Specific guidelines for EU member states to accelerate permitting are expected at some point over the next two years, according to a timeline issued by the European Commission, but that might come too late for country’s still struggling to allay driver anxiety over EV driving range.

Overall, EV adoption is occurring at a much faster rate than the media portray. Five percent represents a crucial threshold before adoption hits the mainstream part of the S-curve. Today, some 31 countries, accounting for two-thirds of the worlds car sales, have surpassed that critical point. While margin pressure is a concern for EV manufacturers, low prices are vital if EV sales are to accelerate.

It’s understandable for individual consumers to rail against government mandates forcing them to drive an EV. True adoption will only happen when individuals feel that the EV network offers better value than the incumbent. History suggests that the best way for that to happen is for governments and the EV supply chain to roll out publicly available EV charging infrastructure, removing any barriers that prevent the network from being built, and allowing individuals to make the choice themselves.

The slowdown in EV sales is likely to be a mere bump in the road towards much broader EV adoption.

Exponential

“Our society is being propelled forward by several new innovations - computing and artificial intelligence, renewable electricity and energy storage, breakthroughs in biology and manufacturing. These innovations are improving in ways that we don’t yet fully understand. What makes them unique is the fact they are developing: at an exponential pace, getting faster and faster with each passing month.”

https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/aa21aa97-eea2-45b4-8686-ae19d8939161/GlobalEVOutlook2024.pdf

https://potentialenergycoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/EV-Report.pdf

https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/transport/if-you-build-it-they-will-come-lessons-first-decade-electric-vehicles

https://statzon.com/insights/ev-charging-points-europe