Why Canada should reform its carbon tax

Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 4,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow my posts on LinkedIn. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents [Start here].

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 8 mins

On the 15th of July millions of Canadian households received a tax-free payment from the government as the proceeds of the federal carbon tax were redistributed.

It’s always nice to get a tax refund, especially when its unexpected. Even better when households can bask in the warm glow that they helped Canada reduce its impact on the environment, and at no cost to themselves.

What’s not to like about putting a ‘price on pollution’, and then not having to pay it?

Yet despite the obvious attractions, the opposition Conservative Party plan to scrap the scheme if they get elected, and they currently hold a 20 point lead over the incumbent Liberal Party.

What’s going on? Let’s dive in and peel back the layers to understand why this policy has promoted such hostility.

The false promise of a climate dividend

Recall that the Canadian federal government requires that 90% of the proceeds from the carbon tax are returned to households in the province or territory where they are collected. This tax-free sum is designed to help eligible individuals and families offset the cost of the carbon tax.

Households receive a refund every quarter directly into their bank account, with the sum based on where they live (provinces consume a very different fuel mix), and the size of their household. The other 10% is used to fund programs that help communities and institutions (e.g., schools, hospitals, municipalities) reduce their fuel consumption.

The federal carbon tax started at C$20 per tonne CO2e in 2019 and has increased by C$10 per tonne each year until C$50 per tonne (€34) in 2022. From 1st April 2023 onwards it began increasing by C$15 per tonne (€10) each year. In April 2024 it increased to C$80 per tonne and is set to continue to rise each year until it reaches C$170 per tonne (€116) in 2030.

By refunding the majority of the proceeds the government reasoned that the carbon price would deliver all of the benefits, but with none of the costs - politically, financially or otherwise. A ‘climate dividend’, as it’s often called it, has long been advocated by some economists who suggest its a way to avoid the social tensions associated with carbon pricing.

Poor communication means few know about, much less understand it

A climate dividend sounds good, but it presupposes that the government has done a good job in communicating it to people. If they haven’t then the costs and benefits are unclear.

A survey conducted at the beginning of 2024 found that only 49% of eligible Canadian adults believed they had received the rebate, with 86% of those associating it with the carbon tax. Overall it means that less than half of the population (48%) could correctly identify the link with carbon pricing.1

One problem was the name of the rebate. Up April it was known as the Climate Action Incentive Payment (CAIP). Nothing to indicate a link to carbon pricing. Nothing to suggest you are getting some of your money back. The government has taken on board this feedback and since renamed it the Canada Carbon Rebate (CCR).

Approximately four out of five eligible Canadians receive more from the rebates than they pay in carbon tax. Unfortunately, no one seems to realise. The same survey found that 43% of people believe that they would be better off if the carbon tax was scrapped, more than double (20%) the number who felt they would be worse off. The average amount people felt they would save if the tax was scrapped was C$1,226 per year.2

Failure to address barriers to switching

The logic of putting a price on carbon is the Polluter Pays Principle (PPP). By incorporating the cots of the externality, carbon pricing acts as a signal to consumers as to which products are more or less carbon intensive. In theory this should encourage them to switch to a less carbon intensive alternative.

Over 300 of Canada’s top economists have chimed in to support the government’s position on carbon pricing. In an open letter published in March the economists address five of the main claims levelled by critics. In addition to addressing its impact on emissions, the cost of living, and businesses competitiveness, and whether carbon pricing is even necessary, the letter also responds to concerns about rebates, echoing the theory of the PPP:3

Critics’ Claim #3: It makes little sense to have both a carbon price and rebates.

What the evidence shows: The price-and-rebate approach provides an incentive to reduce carbon emissions (due to the price), while maintaining most households’ overall purchasing power (due to the rebate).

Carbon pricing works by raising the price of carbon-intensive products, so consumers and businesses are incentivized to adopt lower-carbon options, such as smart thermostats, heat pumps, or hybrid/electric vehicles.

Giving back most of the carbon-pricing revenues in rebates doesn’t undermine this goal; consumers still have the incentive to reduce emissions. The rebates just ensure that most households come out ahead, because they receive an amount back that is slightly above what the average household spends on carbon pricing. Those that reduce emissions the most will come out further ahead; they will pay less in carbon fees but still get the full rebate.

However, the paper fails to address the barriers that prevent people from switching in response to the carbon price. For example, although there may be alternatives that save households money on their fuel bills - heat pumps, electric vehicles, etc. - many of these solutions involve households stumping up significant upfront expenses, even more challenging for lower income households that may not be able to access finance on good terms. Noting these concerns a recent paper co-written by Joseph Stiglitz, argues that the political success of carbon pricing will be measured not by the amount of money it returns to consumers, but by the degree to which it enables them to switch:4

To many, the application of the polluter-pays principle only seems fair if they, as polluters, indeed have an economically viable choice not to pollute. On balance, to secure sufficient support for carbon pricing policies, it seems like their design needs to be attuned more to enhancing people’s ability for switching towards low-carbon substitutes – especially in times of high inflation and high interest rates.

The perception of political machination, real or otherwise

In Europe must learn from Canada's 'price on pollution' debacle, I outlined why Europe needs to learn from the other countries as it seeks to expand carbon pricing to cover transportation and buildings, while also cushioning the impact on lower income households.

The problem with rebates is that even in the best will in the world, it’s very difficult for individual households to be sure whether they have received their fair share or not. There is an inherent risk that one group will feel that it is being unfairly penalised relative to another, especially so if there is blatant electioneering:

In October Prime Minister Trudeau announced a package of measures designed to ease the pressure on low income families. The government would introduce an almost immediate three-year pause on the carbon price for home heating oil, while increasing the carbon tax rebate for people living in rural areas from April 2024. Although the exemption applies across Canada, only about 3% of the population use heating oil to heat their homes, but a disproportionate number of lower-income families burn it on the Atlantic coast. It’s here that Trudeau’s Liberal party also has a strong contingent of parliamentarians.

Carving out a blatant politically motivated exemption to the carbon price has understandably provoked a backlash. An exemption for one part of the electorate is likely to provoke pressure for exemptions elsewhere. It has put the policy under the spotlight ahead of the next general election - likely to take place in 2025 - when it needn’t have been. The opposition Conservative party plan to scrap the carbon tax if they get elected, and currently they hold a significant poll lead over the Liberals. The uncertainty is likely to mean that households and industries considering how they might cut their carbon emissions will now put their plans on ice until after the election.

Revenue recycling also has an economic cost

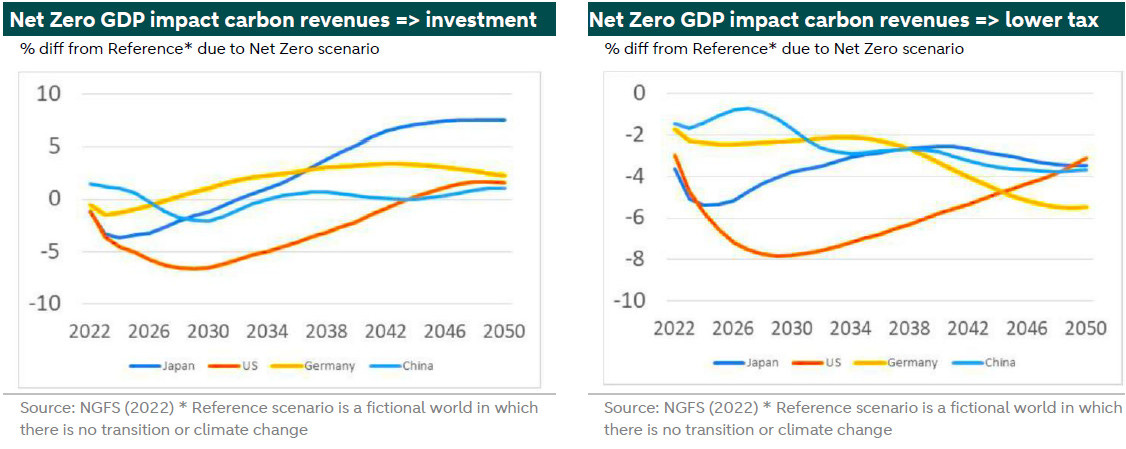

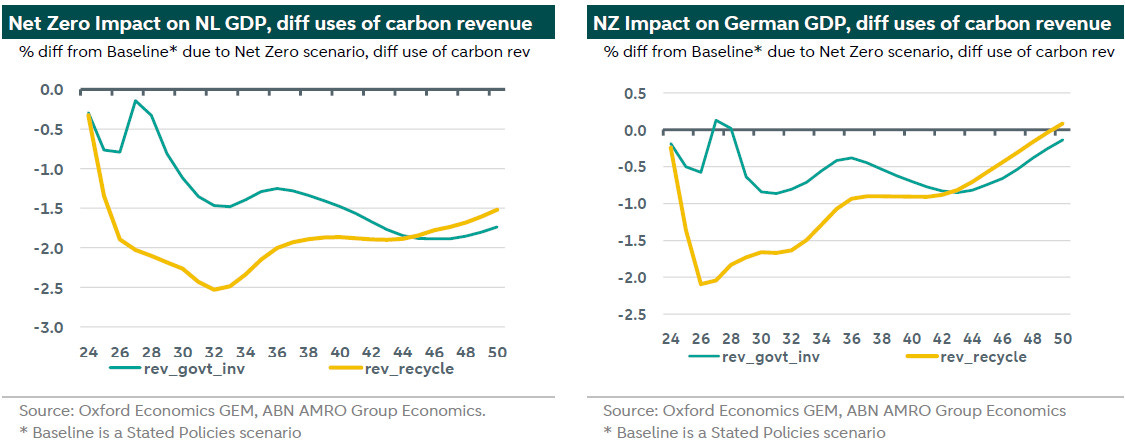

A recent report by ABN Ambro compares the economic impact of carbon pricing depending on whether the revenues are returned to households, or used to increase government investment. Comparing analysis undertaken by the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) with their own research using the Oxford Economics GEM model, they find that adverse impact on headline GDP is significantly reduced when carbon pricing revenues are used for government investment, rather transferred back to households.5

The basis for their conclusion rests on the fiscal multiplier of government investment being greater than that of an income transfer to households. For example, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that a shock to public investment equal to 1% of GDP has an estimated multiplier equal to 1.3% of GDP in the short term, and 2% of GDP after one year:

Although compensating households would limit the damage to private consumption from higher carbon prices and inflation in the short term, the upward impact on total GDP growth would be moderated by the fact that households probably will save part of the extra income…. On top of that, part of consumer spending will be on imported goods, which also reduces the impact on EU GDP, whereas governments can actively chose to spend locally.

Carbon Risk is an advocate for carbon pricing of course, but there is always room for improvement. The Canadian Government should reform the carbon tax, and while they should support those least able to afford it, they should also commit to redistributing the bulk of the proceeds into funding measures that actually help households switch to lower carbon alternatives.

👋 If you have your own newsletter on Substack and enjoy my writing, please consider recommending Carbon Risk to help grow this amazing community of readers! Thank You!👍

https://abacusdata.ca/carbon-tax-pollution-pricing-carbon-action-incentive-payment-abacus-data-polling/

https://distribution-a617274656661637473.pbo-dpb.ca/7590f619bb5d3b769ce09bdbc7c1ccce75ccd8b1bcfb506fc601a2409640bfdd

https://ecofiscal.ca/2024/03/26/open-letter-carbon-pricing/

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4800442

https://www.abnamro.com/research/en/our-research/esg-economist-economic-impact-of-carbon-price-sensitive-to-how-revenue-is