Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 3,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow my posts on LinkedIn. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents.

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 8 mins

Over the past few weeks, two of Australia’s largest nickel suppliers, BHP and Wyloo Metals, have called on the London Metal Exchange (LME) to do more to differentiate between so-called “dirty” nickel and clean, low-carbon nickel supply.

The words of Andrew Forrest, the billionaire owner of Wyloo Metals, illustrate the exasperation that many in the industry feel as they seek to remain competitive against cheap, dirty nickel from Indonesia - the dominant global supplier of nickel:

“We have got to differentiate between dirty nickel and green nickel. The LME must differentiate between dirty and clean. They are two different products, they have two vastly different impacts,”

Meanwhile, BHP’s latest Economic and Commodity Outlook questions whether the LME’s Responsible Sourcing Policy is fit-for-purpose, given the increasingly well–known ESG concerns stemming from Indonesia:1

“The LME’s current policy towards responsible sourcing is narrowly defined, limiting its scope to certain risks both at the point of production which is typically the refinery (health & safety and environmental management system standards focussed) and to due diligence with the upstream metals supply chain (human rights, conflict and financial crimes focussed). Critical ESG risks such as biodiversity, Indigenous rights, tailings, GHG emissions profile and environmental due diligence are not in scope.”

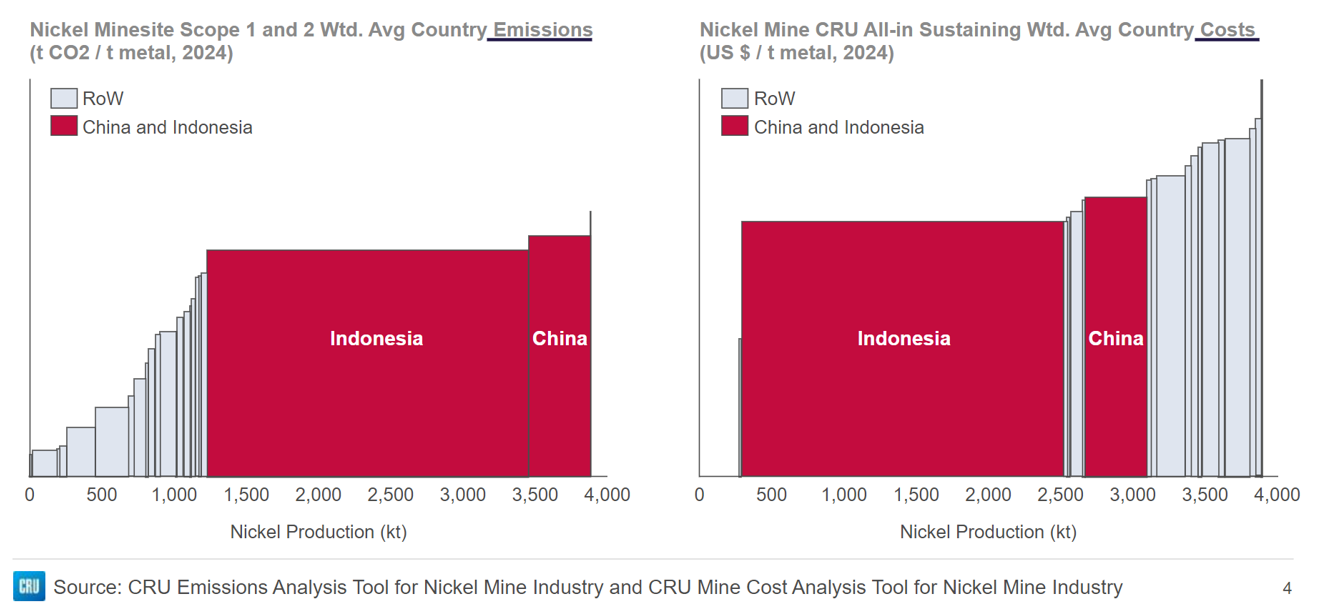

The issue has been thrown into the limelight following the steep drop in the price of nickel over the past year. In the twelve months to mid-February, the price of nickel declined by almost 50% to $16,000 per tonne. Weak demand from China’s construction sector combined with slower than expected growth in EV sales has played a part. The most important factor though has been a surge in supply from Indonesia, partly supported by Chinese investment in local nickel smelting capacity.

Nickel prices have subsequently rallied to over $18,000 per tonne over the past week or so, but the industry remains under intense pressure. The deep bear market has forced suppliers of less carbon intensive nickel such as BHP and Glencore to cut production and even shut down unprofitable mines. However, things could get worse. Christel Bories, the head of French nickel miner Eramet, recently warned that Indonesia’s low-cost, high carbon intensive nickel gives them an unfair competitive advantage, one that they will use to dominate the market, and in turn drive clean nickel suppliers out of the market by the end of the decade (see Commodity markets begin to price carbon risk).

In response, BHP, Wyloo Metals and others have been pushing the LME to differentiate between clean and dirty nickel supplies, by launching a separate contract for clean nickel. They argue that the current LME nickel contract fails to provide an adequate reward for cutting carbon emissions from their production operations. Instead, they believe that clean nickel should trade at a premium to dirty nickel, a so-called ‘green premium’.

The LME ultimately rejected the miners request to create a separate contract, arguing that; a) the market isn’t large enough to “attract sufficient stocks and trading volumes to be viable,” b) continued uncertainty over how exactly to define clean nickel, and c) it would be more efficient to resolve the green premium question through a separate price index reflecting negotiations between buyers and sellers over the value of their green credentials.

The nickel market is only the latest commodity to wrestle with how best to reward low-carbon production. Every other commodity business will have to consider how it can reduce its carbon intensity - if it isn’t doing so already. Simply because a commodity is essential to delivering the energy transition does not mean that it can escape public scrutiny. Failure to address climate concerns will just fuel further accusations of greenwashing (see 'Green' lithium).

Nevertheless, there some commodities that are a step ahead of the game when it comes to using prices to signal climate credentials. Before we get to them and what makes them unique, we need to do a deep dive into the world of the green premium.