Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 4,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow on LinkedIn and Bluesky. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents [Start here].

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 9 mins

“Small forest fires periodically cleanse the system of the most flammable material, so this does not have the opportunity to accumulate. Systematically preventing forest fires from taking place ‘to be safe’ makes the big one much worse.”

-Nassim Nicholas Taleb, Antifragile: Things That Gain From Disorder

As wildfire continues to ravage much of Los Angeles Country and the surrounding areas, attention has inevitably turned to who or what was to blame, and what could be done to prevent a similar tragedy happening in the future.

Every wildfire is different, but it would be remiss not to learn from the experience of other countries also affected. With that in mind please check out the article below. It was originally published in September 2023 behind the paywall but is now free to view.

Controlled (also known as prescribed) burning which cleanses the area of the most flammable material, and preventing it from accumulating, takes place in several countries prone to wildfires, for example Australia.

California has ramped up controlled burns from 135,000 acres in 2021 to 260,000 acres in 2023, and currently plans to burn around 400,000 acres in 2025. Patrick Brown from the estimates that California should be doing almost 8 times as much as it currently does to achieve the maximum economic benefit from wildfire suppression.1

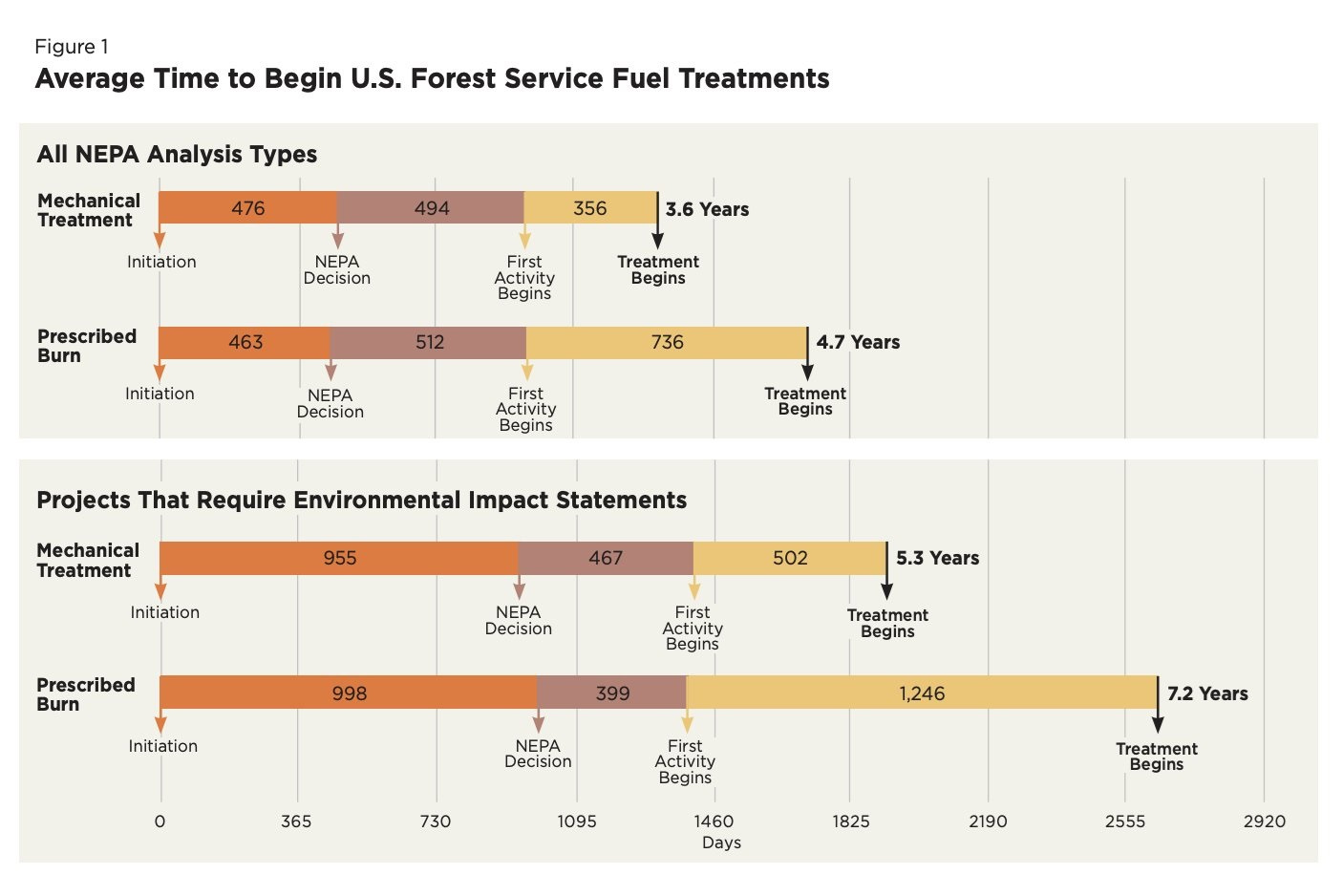

Of course, what works in one environment may not work in another. The physical environment, climatic conditions, population density, and politics all have a bearing on what’s possible. But in California, and the US more broadly, it’s often America’s own environmental regulations that get in the way. For example, analysis by the Property and Environment Research Center (PERC) estimates that is takes between 4.7 and 7.2 years just to get approval to carry out a controlled burn.

When we look back at what made the headlines in 2023, wildfires are likely to feature as one of the most important news stories of the year. From the Canadian forest fires that belched orange smoke over New York, to Greece which experienced the largest ever recorded wildfire in the EU, and to the deadly blaze on the Hawaiian island of Maui.

Climate scientists believe that a warmer world coupled with land-use changes mean that extreme wildfires are likely to become more intense, increasingly frequent, and afflict areas of the world not currently use to dealing with fire risk. According to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), the global incidence of extreme fires is projected to increase by up to 14% by 2030, 30% by the end of 2050 and 50% by the end of the century.2

In addition to the risk to human life and livelihoods, wildfires result in massive plumes of carbon emissions and a loss of biodiversity.

When wildfire intensity rises to extreme levels, dead organic material that would otherwise decompose is burnt under the high temperatures. Instead of carbon being sequestered into the soil, it is released into the air. Intense wildfires also destabilise the soil, breaking off carbon-based organic matter from minerals and killing soil bacteria and fungi.

Global emissions from wildfires in 2023 are estimated to be the third-worst on record, according to Copernicus, the European earth observation agency, covering data for the first eight months of the year. The Canadian wildfires accounted for more than one-quarter of the global total.

Where there’s smoke, there’s fire

Governments typically start trying to mitigate fire risk in the wrong places. The initial step is better predictions. A better fire-forecasting system would of course have enormous benefits. It would enable firefighters to put fire breaks in place, position expensive fire planes in the right locations, all the while minimising the risk to life and property.

However, if you thought weather forecasting was complex, predicting the path that wildfires take is on another level. To stay one step ahead of the fanning flames you need to simulate the wind direction, temperatures, humidity, soil temperatures and dryness, the amount and type of flammable material, as well as the potential reflexive impact that the wildfire, in turn, could have on the weather. And that ignores predicting the most important variable - the source and location of the ignition. Lightning is one of the main causes of wildfires.

The next step governments take is investing in the equipment to douse the fire with water and fire retardants. For example, in the aftermath of the Greek wildfires this year the European Commission announced it will purchase 12 new ‘Canadair’ aircraft to increase the capacity of its aerial firefighting fleet. There’s very little evidence of a correlation between airdrops and fire-fighting success. Aerial firefighting could be more about being seen to do something, rather than nothing at all.

The chances of success are much greater if authorities invest in prevention. Unfortunately no one won an election for preventing a raging wildfire from happening. That being said, we can learn from experiences elsewhere in the world where small fires have long been allowed to burn out in a bid to prevent huge wildfires from occurring.

The tropical savannahs of northern Australia are among the world’s most fire prone regions. The savannas tend to burn in the late dry season, ignited by high temperatures, fanned by strong winds, and fuelled by the build-up of dry tinder. Indigenous communities in Australia had long used fire to manage natural resources. But as indigenous people were forced from or left their traditional lands, the practice stopped, allowing large and intense bushfires to develop.

Controlled burning cleanses the area of the most flammable material, preventing it from accumulating. This form of active fire management means that the savannah is subject to frequent shocks, but one never big enough to be catastrophic. Controlled burning, primarily in the early dry season, helps to protect communities from catastrophic fires and means that significantly less carbon is emitted since there is less biomass available to burn.

It can even play a role in sequestering carbon. A recent study published in the journal Nature Geoscience found that controlled burning can actually lock in, or even increase the amount of carbon sequestered in the soils of temperate forests, savannahs and grasslands. There are two key ways that cooler fires stabilises the carbon within the soil. First off, they create charcoal which is very resistant to decomposition. Secondly, cooler fires encourage the formation of 'aggregates' that increase the amount of carbon bound tightly to minerals in the soil.3

In Australia’s carbon market, Savanna Fire Management (SFM) projects reward planned burning that occurs primarily in the early dry season. Savanna burning programs were reintroduced at scale in the mid-2000’s before being integrated into the carbon market in 2014. Land managers such as traditional owners, park rangers and pastoralists, are offered financial incentives to burn savanna between April and June each year.

SFM Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCU’s) currently trade around A$40-50 (equivalent to €25-30), ~A$10-20 more than generic ACCU’s (i.e., Avoided Deforestation and Landfill Gas projects). Those SFM projects that involve indigenous communities typically trade towards the high end of the range given their perceived co-benefits and higher quality (see Everything you need to know about Australian Carbon Credit Units (ACCUs)).

Burning issues

Savannah fires account for almost two-thirds of gross global emissions resulting from fires. A recent study estimated that controlled burning could cut emissions by 89.3 MtCO2e per year across 37 countries that are covered by savannah. This included 29 in Africa (potentially abating 69.1 MtCO2e per year), 6 in South America (13.3 MtCO2e per year), in addition to Australia and Papua New Guinea (6.9 MtCO2e per year).4

Despite it’s potential to reduce emissions, there is currently no mention of controlled burning as a primary mitigation strategy in any country’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). Australia is the only country that currently includes savanna burning emissions in its national accounts, despite savanna burning being an accountable activity under the provisions of the Kyoto Protocol.

What are the barriers to expanding the practice? As I alluded to earlier, it’s very difficult to persuade people who have grown accustomed to using fire suppression, that fire prevention techniques such as controlled burning are likely to be much more effective. Funding for suppression tends to crowd out money that could be spent on prevention, creating a vicious circle. Bigger and more intense wildfires increase the incentive to spend even more on suppression. For example, controlled burning in British Columbia, Canada has declined significantly since the 1980s as wildfire activity has increased.

But there are other challenges to wider adoption of controlled burning. Funding is required to develop the capacity and infrastructure necessary for controlled burning to take place, such as awareness raising, training, monitoring. There also needs to be suitable governance and other safeguards in place. For example, it’s no use if there are disputes about property rights and no way to settle them.

The appropriate incentives need to be in place. As I outline earlier, Australia uses a regulatory carbon market to enable capital to flow to controlled burning projects. If there are competing land-use demands then it becomes more difficult to introduce, perhaps requiring significantly higher carbon prices to incentivise a change.

The practice of controlled burning may also be unpopular. For example, in parts of Australia such as the north-eastern city of Darwin there have been concerns that the practice is leading to increased air pollution. There is also the chance that a controlled fire might get out of control, although in practice there is little evidence of this occurring.5 6

Carbon credits linked to controlled burning could become increasingly important in the future. Not simply because of how effective they are in reducing emissions and aiding carbon sequestration, but also as a means to reduce the symptoms of a warming world. They are part of a burgeoning type of carbon credit project that includes ‘blue carbon’ projects such as mangrove forests, tidal marshes and seagrass meadows. The latter sequester carbon but also protect vulnerable coastal communities from the vagaries of extreme weather.

👋 If you have your own newsletter on Substack and enjoy my writing, please consider recommending Carbon Risk to help grow this amazing community of readers! Thank You!👍

https://jabberwocking.com/elon-musk-is-the-new-emperor-of-misinformation/

https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/number-wildfires-rise-50-2100-and-governments-are-not-prepared

https://phys.org/news/2021-12-natural-environments-offset-carbon-emissions.html

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-018-04687-7#Sec7

https://theconversation.com/unacceptable-costs-savanna-burning-under-australias-carbon-credit-scheme-is-harming-human-health-186778

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274910041_Prescribed_fire_in_North_American_forests_and_woodlands_History_current_practice_and_challenges