Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 3,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow my posts on LinkedIn. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents.

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 8 mins

In December 2023 the Canadian government announced that it plans to introduce a cap-and-trade scheme on the country’s oil and gas sector. The proposed scheme will cover its upstream oil and gas sector, including its offshore and LNG production facilities. If its implemented on schedule in 2026 it would be the first time that a major fossil fuel producing country has introduced a national oil and gas emissions cap.1

The reasons for capping the sectors emissions are sound. Canada’s upstream oil and gas sector is the country’s largest source of emissions, accounting for around one-quarter (171 Mt CO2e) of the country’s annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in 2019. It is also one of the few sectors where emissions have continued to grow over the past couple of decades (upstream emissions have increased by 21.2% since 2005). Furthermore, emissions are likely to continue to grow in the absence of policy intervention, especially since the industry is looking to expand its LNG capacity, and be ready to take advantage of global energy markets.2 3

Despite the rationale behind introducing a cap-and-trade scheme on the sector, its complexity risks delays and unintended consequences. For example, unlike other more established cap-and-trade schemes such as the EU ETS, Canada’s proposed oil and gas scheme will cover carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide and other GHGs. The measurement, reporting and verification of a wide range of GHG emissions is likely to be very challenging. Methane emissions in particular are very difficult for individual operators to measure, especially considering the possibility of leaks from equipment and pipes.

The cap will also only apply to Scope 1 emissions, i.e., those emissions directly involved on site to produce oil and gas. To ensure a level playing field the cap will also account for the transfer of indirect emissions (e.g., a facility might only use electricity from the grid, or it might use thermal energy or hydrogen from another oil and gas site). Finally, the cap will also take account of emissions that are captured and used in some way (e.g. enhanced oil recovery, permanent storage).

Emissions cap not ambitious enough

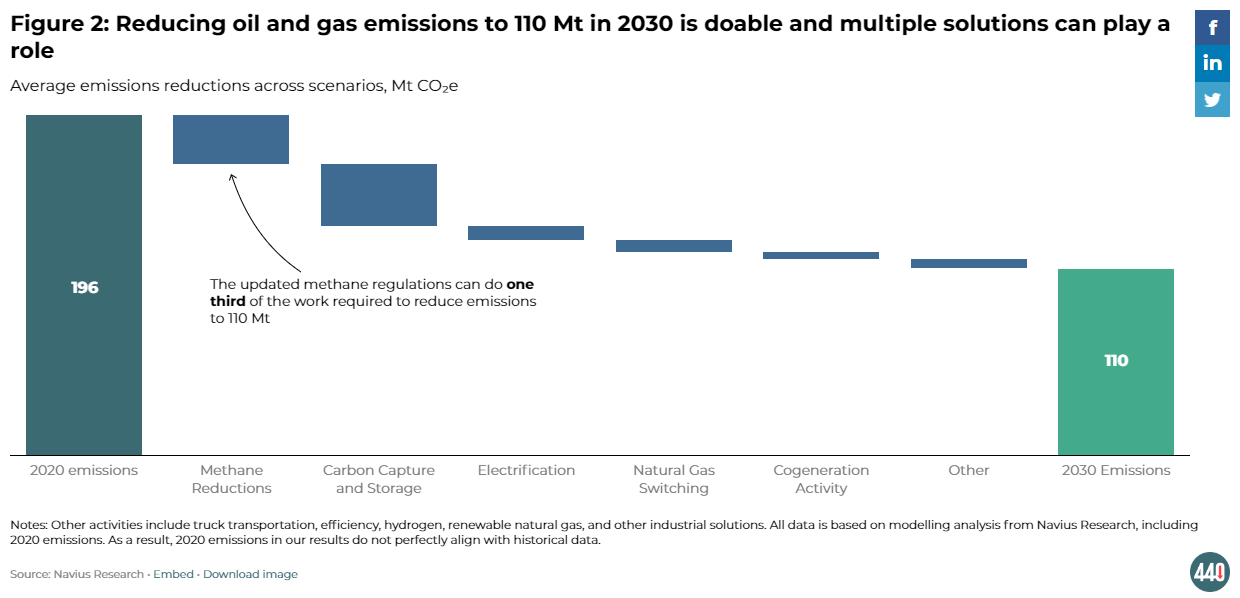

The proposed 2030 emissions cap is between 106-112 Mt CO2e, equivalent to a 35-38% drop in emissions below 2019 levels. Analysis by Navius Research on behalf of the Canadian Climate Institute indicates that reducing methane emissions could deliver one-third of the emission cuts required to achieve the 2030 cap. Carbon capture, use and storage (CCUS) is also expected to play a major role, as well as electrification and fuel switching.4

In setting the cap “slightly below what emissions would be if covered sources achieved technically achievable emission reductions by 2030”, the government are only pushing very softly on the boundaries of what is possible. It’s not a stretch target by any means. For context, the government’s initial modelling suggested that the most efficient pathway to meeting the 2030 target was for the oil and gas sector to cut emissions by 42% by 2030, compared with 2019 levels (see Europe must learn from Canada's 'price on pollution' debacle).