Brazil's carbon market gets the green light

Policy secures the nation's climate leadership among world's biggest oil producers

Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! 🏭

If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access. By subscribing you’ll join more than 4,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. Check out what other subscribers are saying.

You can also follow on LinkedIn and Bluesky. The Carbon Risk referral program means you get rewarded for sharing the articles. Once you’ve read this article be sure to check out the table of contents [Start here].

Thanks for reading Carbon Risk and sharing my work! 🔥

Estimated reading time ~ 10 mins

On 13th November, Brazil’s Senate approved a bill to regulate the country’s mandatory and voluntary carbon markets. Less than a week later Congress, the legislative body of Brazil’s federal government, also approved the proposals. It now only requires the signature of President Lula da Silva to become law.

The debate over the shape Brazil’s regulated carbon market has been going on since 2009. The policies have received renewed impetus as other large countries have either launched their own carbon markets, or have announced plans to do so. For example, emerging economies such as Turkey, India, and Indonesia have begun to implement emissions trading schemes (ETS), partly in response to the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM).

Another factor is Brazil’s return to the world stage following four years of climate policy retreat under the leadership of Jair Bolsonaro. Next year it will be Brazil’s turn to host COP. The 30th edition of the climate conference will be held in the Amazonian city of Belém. Brazil is of course no stranger to holding climate conferences. The first UN conference on environment and development, known as the Earth Summit, was held in Rio de Janeiro in 1992.

The Brazilian government published its latest Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) during COP29. The updated climate plan aims to cut emissions by between 59% and 67% from 2005 levels by 2035, (equivalent to an absolute reduction of 850 million to 1.05 billion tonnes of CO2e), achieved mostly by relying on its carbon-storing forests. As a mark of its ambition it has also been pushing other countries to submit their NDCs by February, the UN’s deadline, while also encouraging governments to bring forward their net-zero target dates from 2050.1 2

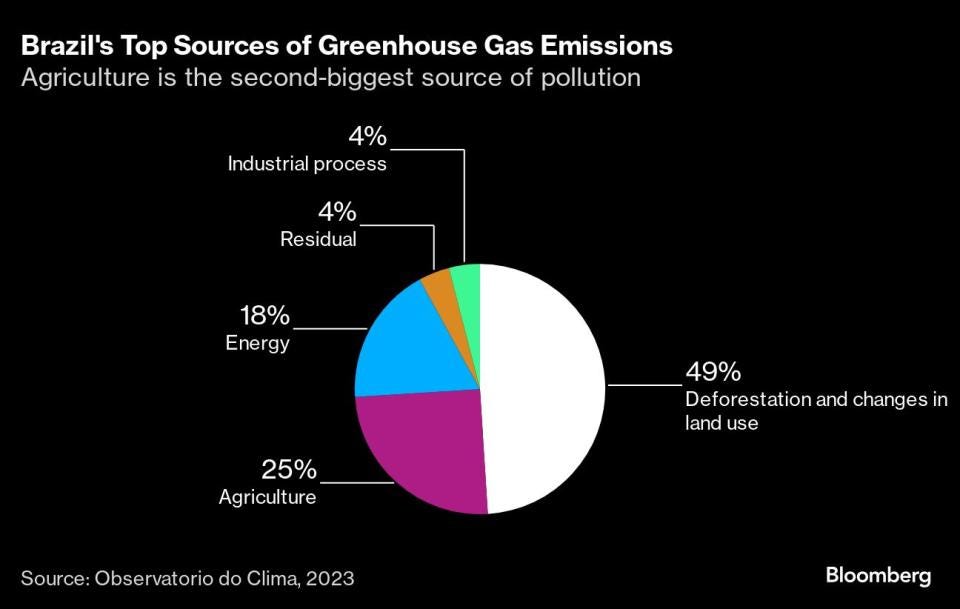

After returning to power in November 2022, President Lula da Silva succeeded in halving the rate of deforestation in 2023, bringing the rate of land clearance in the Amazon down to a five-year low. Land use change is Brazil's largest source of emissions, accounting for almost half (49%) of the country’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, according to Climate Observatory. Forest is often cleared to make way for agriculture, but this is also a major source of emissions, especially methane released by livestock. Overall, agriculture accounts for 25% of Brazil’s emissions (see Repricing deforestation risk in the wake of Brazil's presidential election).3

Nevertheless, beyond cutting deforestation, Brazil will also need to rein in emissions from oil & gas production and heavy industry if it is going to meet its climate targets. A carbon market is the missing link that will help Brazil achieve its carbon ambitions, while also increasing the country’s economic development, and alleviating poverty.

Pricing carbon from oil & gas producers and heavy industry

The ETS will impose reporting obligations on all entities emitting more than 10,000 tonnes of CO2e per year, with those emitting more than 25,000 tonnes of CO2e per year required to meet compliance. These obligated entities will have to surrender allowances for all their covered emissions. Overall, an estimated 5,000 companies are thought to be subject to compliance obligations.

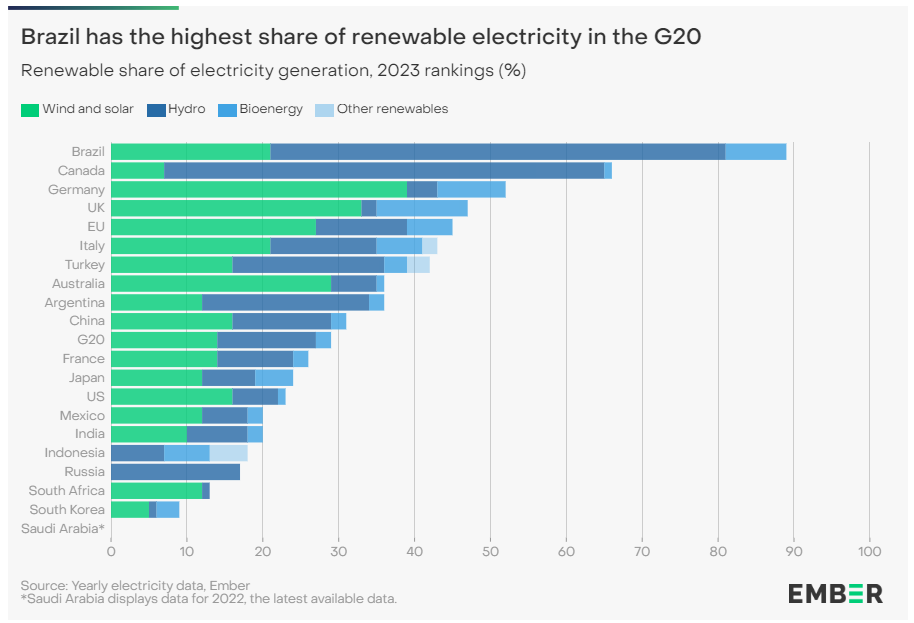

Only around a quarter of the emissions produced in Brazil will be covered by the carbon market, primarily from the oil & gas sector, but also other carbon intensive industries such as cement, iron and steel, and aluminium. In contrast to the EU ETS and other compliance schemes, Brazil has little need to rely on carbon markets to price out fossil fuel power generation. It already has the highest share of renewable energy in the G20 (89%) by virtue of its hydroelectric resources and more recent investments in solar and wind capacity.