Better in than out

The worlds largest meat and dairy corporations are under pressure to cut greenhouse gas emissions

The supply of meat and dairy products is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a small number of huge, multinational corporations. Their influence stretches from the agricultural inputs required to feed cattle, all the way through to the marketing and delivery of the final product to the end consumer.

Up until recently agri-businesses have been able to duck concerns regarding the environmental practices they employ - in particular the significant share of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions that comes from livestock. Their sheer size and influence has been a powerful lobbying force to deflect attention towards the need for food security.

Things are starting to slowly change and global giants supplying meat and dairy are starting to face the same scrutiny normally meted out to fossil fuel companies. A combination of government targets, restrictions on land use, pricing emissions, better reporting of emissions, and action by financial institutions means the industry cannot stay under the radar anymore.

But before we get into all of that, let’s check out just how big an environmental impact the meat and dairy sector has.

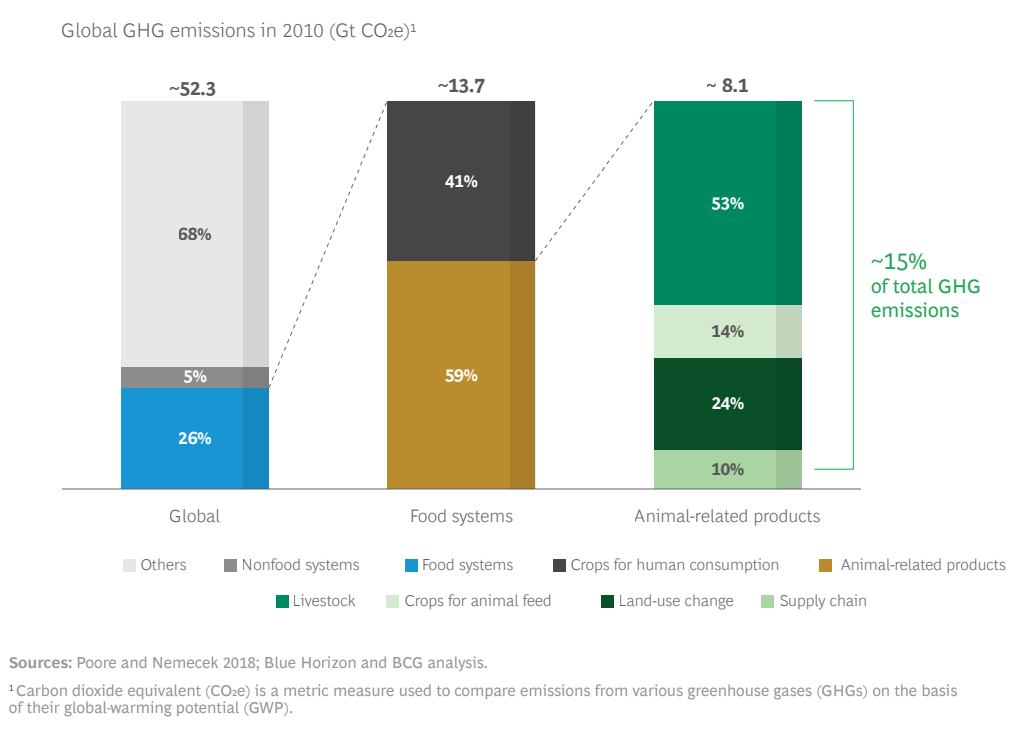

Animal related products are estimated to account for 8.1 Gt CO2e (~15%) of annual global GHG emissions. Livestock account for about half of the emissions, primarily as a result of cattle burping, but also what’s emitted from their manure. The remaining emissions come from activities that support the industry such as the production of animal feed, land-use changes and other supply chain activities.

Around half of the annual greenhouse gas emitted is methane. Recall that methane is one of the most potent greenhouse gases, trapping ~34 times as much heat in the atmosphere over a 100 year period than carbon dioxide. However, over 20 years methane’s global warming potential is estimated to be ~85 times greater. CO2 and nitrous oxide both account for around one-quarter of the sectors emissions, however the latter is significantly more potent. Nitrous oxide has almost 300 times the warming potency as CO2 yet also lasts in the atmosphere for a long time (~120 years).

Total GHG emissions arising from the 15 largest meat and dairy companies combined is estimated to be 734 Mt CO2e (~10% of global GHG emissions from animal related products), according to the Changing Markets Foundation. By far the largest company in the top 15 is JBS. The Brazilian company is the worlds largest meat producer and the third biggest food and beverage company by sales. Overall, JBS is responsible for around 40% of the total emissions produced from the 15 companies outlined in the map below.

Together the emissions from these 15 companies exceed those of major fossil fuel companies such as PetroChina, ExxonMobil, BP and Shell. While oil and gas majors have been under sustained public pressure to reduce their emissions, large meat and dairy companies have not received the same level of scrutiny, despite their comparable emissions.

Governments are typically reluctant to curb the activities of the agricultural sector. A reluctance to threaten their food security, raise affordability issues among consumers, and risk threatening important export industries explain some of the limited action among governments. The agricultural sector also tends to be a powerful lobby group, whether your country is rich or poor. However, the increased concentration of power among fewer but bigger meat and dairy companies adds to the lobbying pressure.

Overall, government policy activity remains far too slow and patchy. However, things are starting to change for the better, with some early signs that it is prompting companies to trial new solutions to cut GHG emissions. Lets look at four of the initiatives and how companies are responding.

1. Global Methane Pledge: At the UN COP26 in Glasgow 2021, 125 governments committed to cutting methane emissions by 30% by 2030, compared with 2020 levels. The commitment is known as the Global Methane Pledge. So far at least action has focused on limiting methane emissions from other sectors of the economy, namely the oil and gas sector in the United States. The signatories have yet to outline detailed plans as to how they will deal with livestock methane emissions.

In the past week, Danone announced that it will cut methane emissions from its fresh milk supply chain by 30% by 2030. The dairy conglomerate, one of the top 15 meat and dairy corporations, works with 58,000 dairy farmers across 20 countries. It is the first company to set targets in line with the Global Methane Pledge. Other meat and dairy corporations are likely to be follow in Danone’s wake with similar commitments. However, so far at least the company has been light on details as to how it will achieve these targets.

2. Restrict land use: Governments can act to curtail emissions from the sector by restricting the growth in land used for grazing cattle. This is especially concerning in Brazil which has been plagued by deforestation, much of it illegal. President da Silva, elected into office in October 2022, campaigned on a pledge to eliminate deforestation of the Amazon (see Repricing deforestation risk in the wake of Brazil's presidential election).

It’s also a policy that’s being considered in Europe. In 2022 the Dutch government announced plans to buy out up to 3,000 farms and major industrial polluters near protected nature reserves with the aim of cutting the country’s nitrogen emissions in half by 2030. Getting emissions under control may require slashing livestock numbers by 30% (35 million animals) by 2030, according to projections by the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency.

In response to the Dutch governments plans, FrieslandCampina, the Dutch multinational dairy company announced that it would be trialling a technology which seeks to close the mineral cycle on a farm, cutting nitrogen emissions by up to 70% and reducing the need for artificial fertilisers.1

3. Pricing methane emissions: Later this spring, the New Zealand government is expected to announce the rate at which methane emissions from livestock will be charged. The nation, which has 7-times more residents on four legs than two, and where half of its GHG emissions comes from agriculture, will be the first to introduce such a levy. The charge is expected to be phased in over 5 years from 2025 to allow farmers time to respond (see Pricing methane emissions out of the atmosphere: America's first nationwide price on a greenhouse gas does not go far enough).2

Fonterra dominates the market in New Zealand. Pressure to cut methane emissions and the threat of levies being imposed by the government in the near future have incentivised the dairy giant to invest in new technology. The company’s scientists have developed a natural additive, which when it comes to market before 2025, can be fed to calves and will reportedly cut their methane emissions by 20%.3

4. Smarter emissions reporting: Governments are likely to begin enforcing better monitoring and regular reporting of emissions, especially as securities regulations are beginning to act against ‘greenwashing’ claims. Of the 15 companies, only 6 report their full Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions with a further 2 reporting partial Scope 3 emissions, according to the Changing Markets Foundation. Three companies do not report any emissions data (see Owning up to Scope 3: How investors should think about the SEC's proposed disclosure requirements).

Despite the importance of methane to overall GHG emissions from the sector, the quality of the methane emissions data is even more patchy. Not one of the 15 corporations reported their methane emissions. As part of its commitment under the Global Methane Pledge, Danone has also committed to report its methane emissions as part of its “extra financial disclosure” information it provides to investors.4

5. Divestment: In the same way that financial institutions are under pressure to divest their portfolios of fossil fuel companies, they are also being pushed to reallocate capital away from meat and dairy corporations because of their high GHG emissions. This is something that will become more acute once there is more rigorous emissions disclosures in place by listed companies (see Whack-A-Mole: How patchy global carbon markets channel fossil fuel finance).

A new report from Planet Tracker and the Changing Markets names the 20 investors and 20 banks currently financing the methane-generating activities of the 15 largest global meat and dairy companies. The aggregate methane footprint attributable to the top 20 equity investors is 68 Mt CO2e, while the footprint is roughly three times as large for the top 20 banks (202.5 Mt CO2e). Morgan Stanley takes the top slot (40 Mt CO2e), followed by JP Morgan (31 Mt CO2e) and HSBC (19 Mt CO2e).

The rationale for divesting hangs on the same thread as it does for fossil fuel companies. By cutting access to finance, the cost of producing carbon intensive meat and dairy products will increase. This could then give lower carbon alternatives a greater competitive edge. In addition, advocates argue that by removing their social license to operate, it breaks the meat and dairy corporations influence on both investment institutions and government.

The overall impact of all of these measures will be to raise the cost of producing conventionally produced meat and dairy products relative to their low carbon alternatives. This could mean that alternative protein products such as plant-based or cultivated meat, achieve cost parity with conventional meat and dairy much sooner.

Moving forward, investors should monitor progress on the 5 instruments that are being used to leverage change, and importantly how those companies most exposed to this risk are responding. As with other carbon intensive industries, it may be those that can decarbonise faster than the competition that stand to gain the most.

https://www.dairyreporter.com/Article/2022/07/26/frieslandcampina-lely-and-rabobank-launch-nitrogen-pilot

It’s not clear at this stage what the levy will be. Keith Woodford, an expert on the New Zealand dairy industry has suggested that NZ$100 per tonne of methane, equivalent to $65 per tonne ($2.60 per tonne of CO2e). This seems way too low.

https://keithwoodford.wordpress.com/2022/11/30/moving-forward-with-methane-levies/

In contrast, the US methane emissions charge begins in 2024 at $900 ($36 per tonne of CO2e), increases to $1,200 ($48 per tonne of CO2e) in 2025, and will rise to $1,500 a tonne ($60 per tonne of CO2e) in 2026.

https://www.irishexaminer.com/farming/arid-40995731.html

https://www.just-food.com/news/danone-commits-to-a-30-cut-in-methane-emisions-by-2030/?utm_source=pocket_reader