Welcome to Carbon Risk — helping investors navigate 'The Currency of Decarbonisation'! If you haven’t already subscribed please click on the link below, or try a 7-day free trial giving you full access.

By subscribing you’ll join more than 3,000 people who already read Carbon Risk. You can also follow my posts on LinkedIn and benefit from my referral program. Thanks for reading!

Estimated reading time ~ 8 mins

The mining industry is particularly exposed to new regulations that mandate companies report on their Scope 3 emissions, and rising pressure from banks and investment institutions to cut their ‘financed emissions’.

Mining is responsible for 5 Gt CO2e in Scope 1 and 2 emissions; 90% of which is fugitive coal-bed methane released during coal extraction. Yet Scope 3 emissions dwarf those emissions directly within miners control.

Almost 10 Gt CO2e of Scope 3 emissions are released due to thermal coal combustion involved in generating electricity and the use of met coal to manufacture steel. While around 4 Gt CO2e arise from gas combustion used to process metals and to manufacture mining equipment, etc.

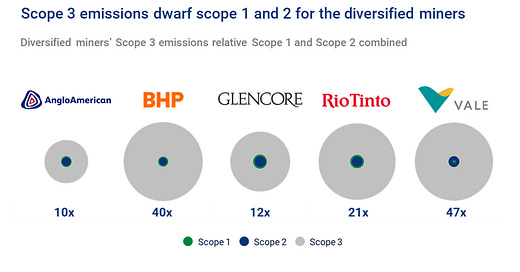

Scope 3 accounts for ~70% of overall mining emissions, but for many of the largest miners it represents 90-95% or more of their emissions. The top seven global mining companies have combined Scope 3 emissions equivalent to 4% of global GHG emissions. These industry behemoths - multi-nationals like Rio Tinto, BHP, and Vale - are under more climate scrutiny than ever before.

It gets worse. If business continues as usual, the industry’s Scope 3 emissions will rise sharply. Global extraction of raw materials is expected to increase by 60% by 2060, according to The Global Resources Outlook 2024 report, due to be published by the UN in February. The composition of that growth in resource demands, and thermal coal’s share in particular, is perhaps even more important than the overall figure when Scope 3 is concerned.1

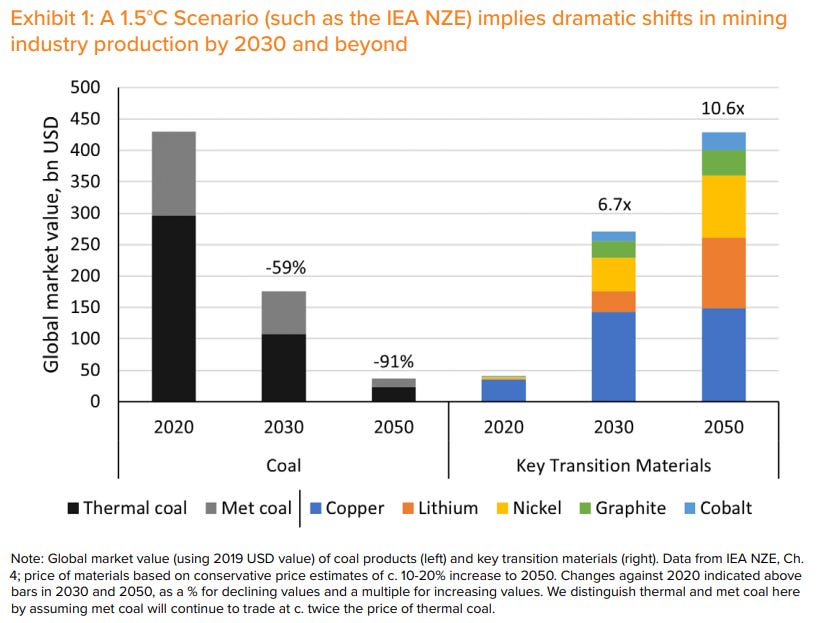

Meeting net zero will require a step change in the commodities that miners are able to extract from the ground. The IEA’s Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario is likely to result in the value of thermal and met coal production falling by 60% over the next six years, and by more than 90% by 2050. At the same time miners are under pressure to deliver the commodities essential to the energy transition (copper, lithium, etc.), whose production value could rise 10-fold by 2050 (see Caution! Net zero scenarios are not forecasts).

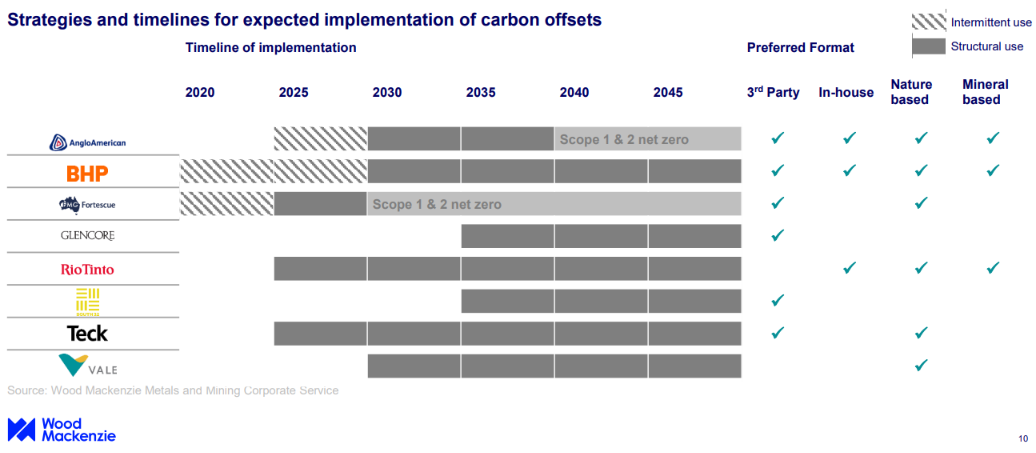

All seven global diversified miners have a goal of reaching net zero emissions (Scope 1 and 2) by 2050 or before, according to analysis by Wood Mackenzie. However, to make a real difference to meeting net zero, the miners will have to tackle their Scope 3 emissions. Five of those miners have set Scope 3 net zero targets for 2050, with Fortescue aiming to achieve this goal by 2040. Nearer term targets are typically focused on particular commodities (e.g., iron ore, coal, etc.), or parts of their supply chain (e.g., shipping).

Constraints play a major role in influencing both the level of ambition and the energy transition strategies employed by the miners. By definition, diversified miners tend to have very different characteristics: the commodities they extract (coal, iron, copper, etc.), the demands from stakeholders in the regions they operate in (Europe, Australia and California are leading on Scope 3 disclosures), and the location of their end customers (major iron ore producers sell to steel mills mostly based in China). Nevertheless, the most vivid way of illustrating the disparity between miners is the ratio between their Scope 3 emissions and combined Scope 1 and 2 emissions. Anglo American and Glencore emit ~10x Scope 3 vs Scope 1+2, versus 40-50x for BHP and Vale.

Divestment is not the answer

Since 2017 many of the major mining companies have divested their asset portfolio of fossil fuels, while since 2022 there has been a push to acquire more energy transition-focused commodities. Although divestment of coal assets in particular has a beneficial impact on an individual company’s Scope 3 emissions, the net impact on global emissions is zero, and it may even be counterproductive.

When a mining company divests of its thermal coal assets, it doesn’t simply close their extractive business, sell the parts for scrap and move on to something greener. They will want to maximize the value they get for that asset by selling it to the highest bidder, often state owned energy companies or private equity groups.

However, divestment is meaningless if the assets are simply transferred to a company less accountable for its environmental performance. Out-of-sight, out-of-mind, but not necessarily out-of-business.

Managed decline

Glencore had been the notable exception to the thermal coal divestment trend employed by many of its peers. Speaking to the Financial Times in 2020, former CEO Ivan Glasenberg outlined the flawed rationale behind divestment:2

“How does that help the world to reach the Paris accord? Those mines are going into the hands of other players who have no intention of reducing Scope 3 emissions and if anything gives them a free hand to start producing more.”

Rather than divest its thermal coal assets, Glencore’s strategy has been focused on gradually running down its coal mines by the mid-2040’s, and using the cash generated from the sale of thermal coal in the meantime, to reinvest in energy transition assets and support the development of low emission technologies. It remains to be seen whether this strategy survives following the late 2023 Glencore acquisition of Teck.

Other miners are reconsidering divestment and adopting a more responsible approach. In 2022 BHP announced that it will close its last thermal coal mine, Mount Arthur near Sydney by the end of 2030. The high cost of decommissioning and anti-coal investor sentiment forced their hand into managing the asset down, rather than divesting.

Higher quality, less carbon

Boosting the supply of high grade iron ore increases the viability of electric arc furnace (EAFs) steel production. This is important since EAFs emit ~0.4 Mt CO2e per tonne of crude steel produced, over 80% less carbon than through a traditional blast furnaces. EAFs require ‘direct-reduced iron’ that an iron content of 67% and above. However, DR-grade iron ore currently makes up only about 4% of global iron ore supply (see Europe's bridge to 'green' steel).3

Australian iron ore miners have long focused on lower-iron content ore (62% Fe) in response to the huge growth in blast furnace-based steel production in China. The quality of the iron ore has been declining over the past decade as mines are depleted, making it even less suitable for DRI processes.

While BHP is pursuing decarbonisation through carbon capture and storage (CCS), Vale, Rio Tinto and Fortescue (the other three major iron ore producers), are increasingly focusing on developing higher-grade iron ores, particularly in Africa and Canada.

Carbon markets, at least for residual emissions

Almost all of the diversified mining companies foresee a role for carbon credits if they are to meet their emission reduction targets, including and especially their Scope 3 commitments.

Last year Rio Tinto admitted that its climate targets were in jeopardy without carbon credits, announcing that it would “build a sustainable and long-term carbon credit portfolio generating 1.7 million tonnes annually by 2030”. The miner plans to co-develop or co-finance high quality carbon projects in those regions where they have significant emissions.

The most notable change since the table below was published in August 2023 is the decision by Fortescue, the world’s fourth largest iron ore miner, to shelve its plans to purchase carbon credits on the voluntary market. In September, the Australian mining giant indicated that it would divert funds previously allocated to carbon credits towards furthering its own decarbonisation.

Even if it succeeds in driving its own Scope 1 and 2 emissions to near zero, it will be much more difficult when it comes to Scope 3. Indeed, as companies realise the extent of the challenge, pressure to use carbon credits to meet Scope 3 targets is likely to intensify. As the carbon credit market continues to mature Fortescue may well be forced to change its mind.

Miners must balance multiple climate goals at the same time, including ones that come into conflict with each other. They are under pressure to stop producing coal and iron ore, but yet they must not give less climate conscious operators a free pass. They need to increase production of resources essential to the energy transition, but they also need the capital that coal and iron provide to deliver on that investment. Finally, they must manage their carbon intensive assets down, but also invest in them to cut their Scope 3 emissions.

As the pressure to cut Scope 3 emissions increases, expect that dilemma to intensify.

Scope creep

This year many of the worlds largest economies are introducing tough climate disclosure laws that require companies report on their entire supply chain. Crucially many of these laws go beyond direct emissions (Scope 1 and 2), and also mandate firms report on their indirect emissions too (Scope 3).

https://www.resourcepanel.org/reports/coming-soon-global-resources-outlook-2024

https://www.ft.com/content/3e778f6f-5008-454b-ab5c-c52adec6576b

https://ieefa.org/resources/solving-iron-ore-quality-issues-low-carbon-steel