Run out of steam

Delay in implementing levy on global shipping emissions leaves decarbonisation all at sea

Last week, the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) agreed to reduce the carbon intensity of international shipping by 40% by 2030, compared with 2008 levels. Governments also agreed to cut total global shipping emissions by at least 20% by 2030, (with an ambition to cut by 30%), reach 70% by 2040 (but striving for 80%), and reach net zero “by or around” 2050.1

It’s worth noting that although the IMO is a branch of the UN, global shipping emissions are excluded from the Paris climate agreement. The reason relates to shipping’s notoriously complex ownership structures whereby ships are often registered in one of a handful of small countries (e.g. the Marshall Islands, Liberia, and Panama), owned in another country (e.g. Greece, South Korea, China etc.), but commissioned by someone else entirely (often commodity exporting nations such as Brazil, Argentina and South Africa or major trading economies like China’s).

Prior to last week’s negotiations, the best the IMO could agree on was a halving in emissions by 2050 compared with 2008 levels and an aspirational goal of net zero. The revised strategy does represent an improvement (i.e. interim targets for 2030 and 2040), however the pace of the decline and the absence of stricter targets falls short of what is required to meet the 1.5°C target set out in the Paris accord. For that to be achieved global shipping emissions must fall 45% by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050 according to the UN.

One of the most important mechanisms to decarbonise shipping to run-aground in the negotiations was a shipping levy on marine fuel. Described as a “maritime GHG emissions pricing mechanism” in the IMO’s strategy paper, the levy will undergo further review over the next few years, but it now looks unlikely that it will be introduced before 2027 at the earliest.

Marine fuel oil will need to face an average carbon price of almost $200 per tonne (€180 per tonne) in order to reach net zero by 2050, according to a report published by the Getting to Zero Coalition, an industry group led by the think tank Global Maritime Forum (GMF):2

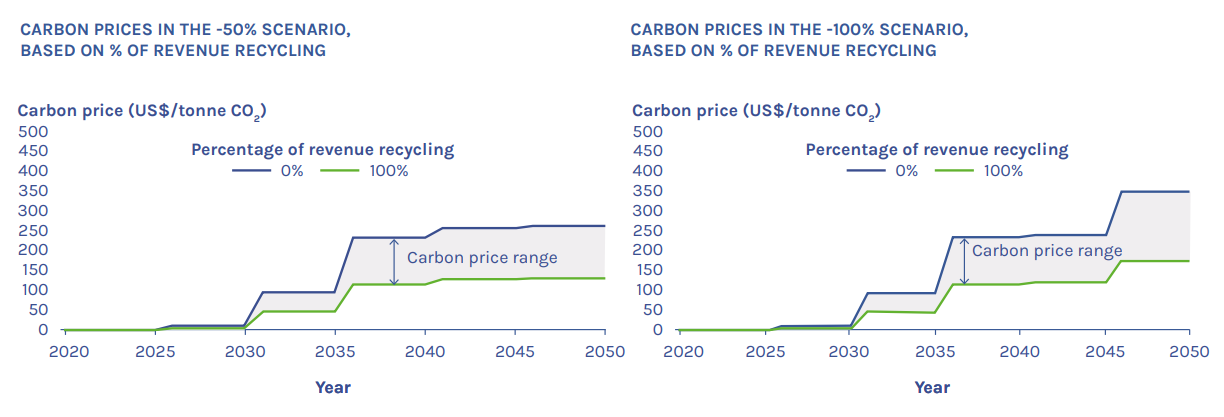

In order to achieve 50% GHG emissions reduction by 2050 compared to 2008 (-50% scenario), the carbon price level averages US$173/tonne CO2. For a 2050 target of full decarbonisation (-100% scenario), the average carbon price would only need to be slightly higher: around US$191/tonne CO2. In both scenarios, according to the model, the price level begins at US$11/tonne CO2 when introduced in 2025 and is ramped up to around US$100/tonne CO2 in the early 2030s at which point emissions start to decline. The carbon price then further increases to US$264/tonne CO2 in the -50% scenario, and to US$360/tonne CO2 in the -100% scenario.

GMF indicated that the carbon price could be half that level if revenues from the levy were ‘recycled’ to further support the decarbonisation of shipping. The ultimate decision on how much can be ‘recycled’ is a political one as funds are also going to be required to help less developed countries manage the cost of the transition:

Depending on the level of revenue recycling, an MBM [market based measure] with global scope in the -100% scenario could be designed to have a carbon price level averaging between US$96-191/tonne CO2 and reaching a maximum of between US$179-358/tonne CO2.

Barriers to switching to zero carbon alternatives in the shipping sector are immense, and unlike other sectors much of the investment needs to go into infrastructure that individual shipping companies have little or no control over. The GMF report estimates that some 87% of the $1.4-1.9 trillion in investment required to decarbonise needs to be directed at land based infrastructure. This includes hydrogen production, ammonia synthesis and storage/distribution.

Despite the disappointing outcome, the IMO’s shipping levy proposal isn’t the only carbon pricing initiative to hit the shipping industry.

Beginning in 2024, the maritime industry will be included under the EU ETS. Ships travelling within the EU (intra-EU voyages) will be required to pay for all of their emissions, while for voyages to or from a non-EU destination, half of the emissions will be covered. Vessel operators will need to purchase EUAs amounting to 40% of their emissions in 2024 (payable by April the following year), 70% in 2025, and reaching 100% of 2026 emissions (see Putting a cap on European shipping emissions: The maritime sector is beginning to price in EU carbon prices).

Due to come into effect one year later, the FuelEU Maritime regulation sets annual targets for the GHG intensity of energy used onboard by a ship or pool of ships. Starting at -2% in 2025 (compared to a 2020 baseline), the emissions intensity target rises to -14.5% in 2035, through to -80% by 2050. A bit like Low Carbon Fuel Standards (LCFS), FuelEU Maritime issues a penalty or reward based on the extent of under or overperformance relative to the annual target (Everything you need to know about Low Carbon Fuel Standards (LCFS)).

European regulations help to influence investment decisions elsewhere in the world at the margin. However, the absence of a global price on shipping emissions means that the cost of decarbonising the sector is likely to be much higher in its absence. The greater the degree of participation among countries, the more likely it is that private sector capital can be allocated to the most efficient decarbonisation technologies. There is little incentive to build out the long term infrastructure necessary if each region faces significantly different price signals.

With vessels expected to enjoy 20 to 30 years of service before being scrapped, the shipping industry are looking to 2050 right now. Any delay in implementing a levy risks low carbon technologies being left to flounder, and less carbon efficient ones being locked in.

The 'sailing ship' effect and the energy transition

The ‘sailing ship’ effect – also known as the ‘last gasp effect of obsolescent technologies’ - occurs where competition from new technologies stimulates improvements in incumbent technologies and the firms that produce them. For example, the advent of steam power inspired the makers of sailing ships to innovate, transform…

https://www.imo.org/en/MediaCentre/PressBriefings/pages/Revised-GHG-reduction-strategy-for-global-shipping-adopted-.aspx

https://www.globalmaritimeforum.org/content/2021/12/Closing-the-Gap_Getting-to-Zero-Coalition-report.pdf