One hundred zettabytes of data was created and consumed in 2022, according to the International Data Group. By 2024 that figure is projected to rise by 50%. Every picture, email, Zoom meeting, ChatGPT request, and Substack article has to be stored somewhere. Our reliance on data storage is only likely to grow as AI’s tentacles proliferate into other parts of our everyday life.

All that data storage is very energy intensive. Server racks produce lots of heat and must be cooled to between 18 to 27 degrees Celsius to ensure they work efficiently. Total power demand estimates tend to come with a wide error band, but latest estimates suggest that global power consumption is between 250-350 TWh. The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that data centres and the transmission networks that underpin the digital economy were responsible for 330 Mt CO2e of emissions in 2020 (0.6% of global GHG emissions), roughly one-third of global airline emissions.

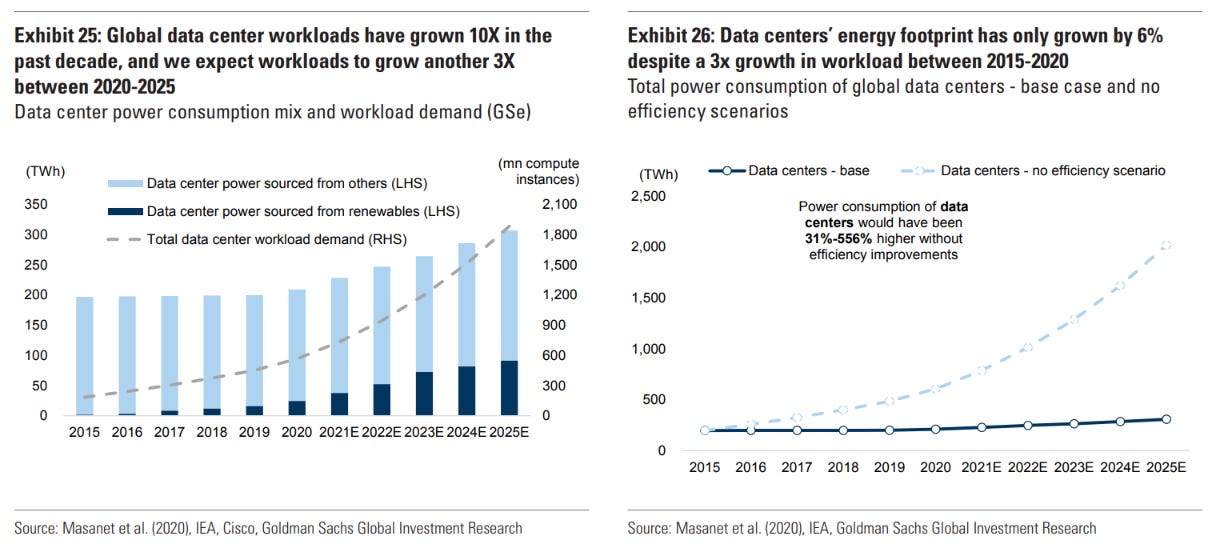

Data centre workload - measured in number of compute instances - grew by 3X between 2015-20. Over the same period power demand from data centres has only increased by 6%. System-level efficiency gains have been crucial in mitigating the impact on overall power demand. Firstly, data centres have been able to get better energy performance from CPU and memory devices, and secondly, chip performance has enabled a migration towards energy efficient hyperscale/cloud services.

According to Goldman Sachs, data centre workloads are projected to rise by another 3X between 2020 and 2025. It might be more difficult to get the same improvement in efficiency over the next few years. The bank expects a significant jump in power demand (~50%) between 2020 and 2025 to 300-350 TWh, but that’s still clearly much less than the increase in data centre workload.1

Part of the reason for this is that efficiency gains have slowed down since 2018. The easy wins gained from consolidation and improvements in cooling systems are now being replaced by much more difficult, incremental efficiency improvements. The other reason is that remote servers today perform three functions: storage, networking and increasingly, processing. It’s this last function that is the most energy intensive of all. Nevertheless, Goldman Sachs estimate that in the absence of any efficiency improvements, power consumption from global data centres in 2025 would be ~ six times higher.

To begin to understand the impact of the cloud on the climate and where it’s going we need to go to Northern Virginia. It’s here where the world of CPU’s and zettabytes collides with carbon markets and the growth in renewable energy. The region, located a short distance from the nations political capital, is the data centre capital of North America, accounting for around 3,440 MW of data centre inventory (45% of US capacity). With another 651 MW under construction, the regions dominance of data centre power demand is set to grow. Northern Virginia’s data storage capacity also towers over the rest of the world. It is over three times larger than the next biggest market, currently Singapore. Overall, Northern Virginia accounts for around one-third of global data centre capacity.2