Carbon risk dulls allure of gold miners

Gold miners have an image problem.

The global metals and mining business is responsible for around 8% of global carbon emissions. In contrast to their compatriots mining copper, silver, tin, nickel and a whole host of other metals and minerals essential to driving the energy transition, gold miners have no such compelling narrative.

The gold mining sector is facing increasing pressure from institutional investors to cut emissions. Arguably they are having to work much harder to earn their place among investors than other metal miners with an energy transition story to tale. If they fail to cut emissions, gold miners risk becoming outcasts, tainted with the same brush as coal.

The average emissions intensity of the top 16 gold miners was 0.81 tons of CO2e per oz in 2021, according to Metals Focus’ Gold ESG Focus 2022. This includes both Scope 1 (on-site activities) and Scope 2 emissions (such as power purchased from the grid).

The top 16 gold miners account for ~30% of global gold production, estimated to be 3,577 oz in 2021. Assuming the emissions intensity of the top 16 gold miners is representative of the rest of the sector that means gold mining is responsible for 93 million tons CO2e of direct emissions in 2021, equivalent to 0.3% of global emissions.

A study by the Centre for Exploration Targeting (CET), based in Western Australia examined the impact of a carbon tax ($50 and $100 per tonne) on gold miners production costs across 35 different gold producing countries.

Although we are many years away from ever realising a global carbon price that doesn’t mean individual gold producers aren’t preparing for greater scrutiny. As in other sectors of the economy, some gold producers are employing shadow carbon prices to help them make decisions in the event that their operations are subject to carbon pricing in the future. (see In the shadows: Everything you need to know about internal carbon pricing).

Analysis of 194 different gold mines revealed that the emissions intensity of the energy source used onsite is the main factor driving differences in overall mining emissions intensity between gold mining countries.

For example, over 80% of Canada’s electricity generation comes from low carbon energy, mainly hydroelectric. In contrast, nearly 85% of Australia’s power comes from fossil fuel sources, while South African mines tend to be powered by electricity generated from burning dirty brown coal.

Previous research by CET found that the grade of gold (i.e., grams of gold per tonne of ore), and the type of mine (i.e., open vs underground) are also key factors. Higher grade gold mines have a lower emissions intensity than lower grade gold mines. Meanwhile, underground mines in Australia and North America tend to have an average emission intensity 40-50% lower than open pit mines.

Although underground mines tend to have a lower emissions intensity than open-pit, very deep mines tend to be extremely carbon intensive. For example, South Africa's underground gold mines are much deeper (many over 2km deep) than underground mines in other countries. These ultra-deep gold mines require considerable energy to cool and ventilate.

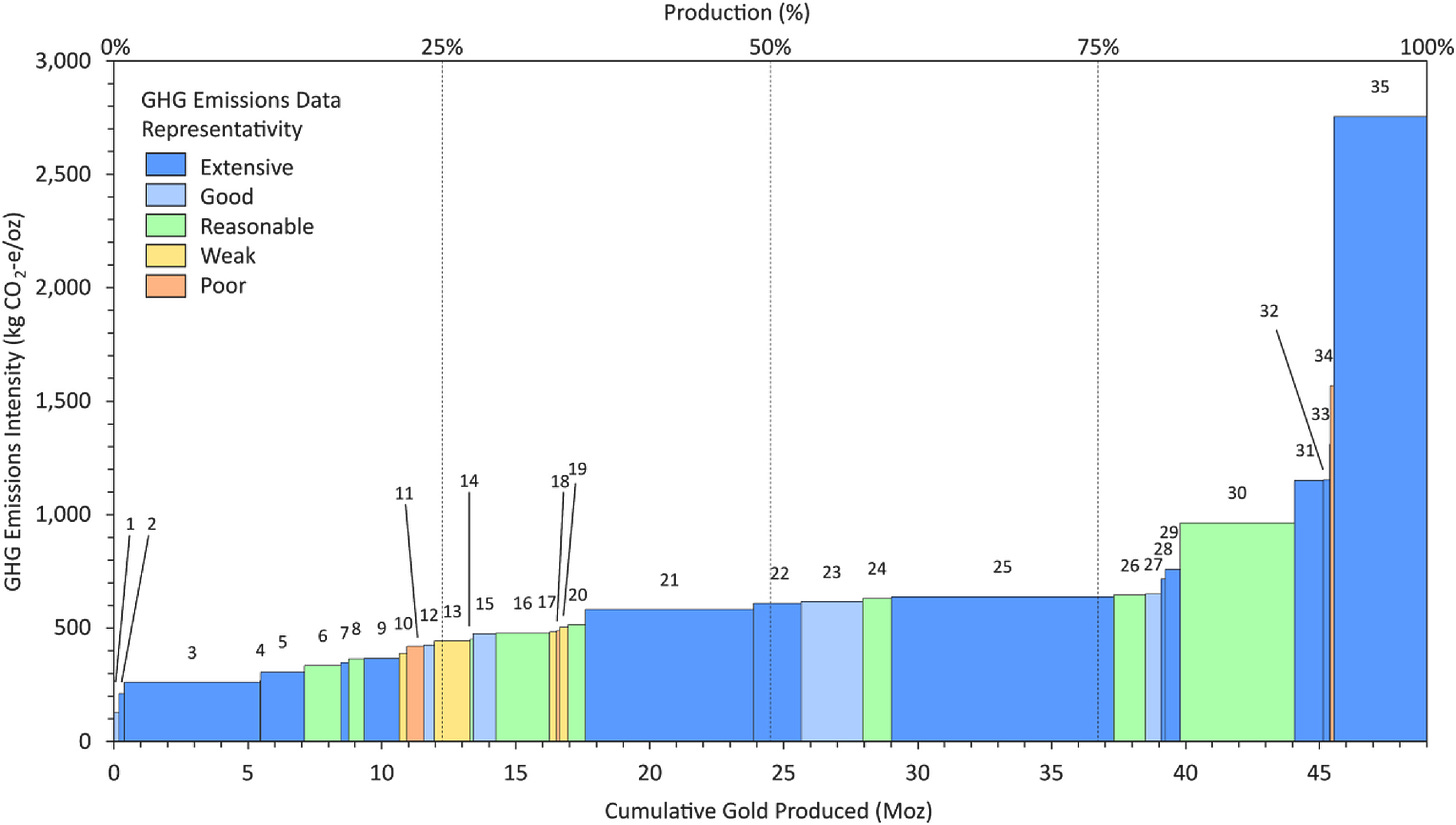

Gold producer emissions intensity curve, kg CO2e per oz

The emissions intensity among the top 16 gold miners has increased by around one-third since 2014, rising from ~0.6 tons of CO2 per oz in 2014 to 0.81 tons of CO2 per oz in 2021. A decline in the grade of gold appears to be the main factor behind the increase, and further declines are likely to push emissions intensity higher.

Despite pumping record amounts of cash into exploration in the early 2010’s, the size of new gold reserve discoveries has slowed. The average grade of new gold deposits has declined from 10 grams per tonne in the early 1970’s to around 1.4 grams per tonne today. Gold grades are expected to get worse as gold miners must exploit ever more difficult seams in order to maintain output.

In Australia the average gold grade is projected to fall by 44% between 2018 and 2029. CET warn that without adapting, the emissions footprint per ounce for open pit and underground mines is likely to increase by 49% and 34% respectively.

What does this mean for investors in gold miners?

The current cost-competitive position of a gold producer does not guarantee its competitiveness in the event that it is subject to a global carbon price. The change in the relative cost positioning of gold mining in different countries is key to assessing financial risks in a climate constrained world. Of the large gold producers only Canada becomes more competitive after a carbon tax is introduced. Australia, Russia and the USA become less competitive.

Change in country gold production cost positioning assuming $100 per tonne CO2e carbon price, % change versus total all-in production costs

Gold extracted from mines with relatively low emissions intensity may start to extract a premium versus gold mined with much higher emissions. Investors may start to incorporate this into their assessment of the value of the gold producer. In particular it may pay to start focusing on those countries on the left hand side of the chart above.

Gold producers have very little control over the grade of the gold, nor whether it is open-pit or underground. However, mining companies and the jurisdictions they operate in can make a big difference to their emissions profile by increasing the proportion of low or zero carbon electricity. Those gold producers that can demonstrate they are able to cut their Scope 2 emissions intensity are likely to be looked on more favourably by investors.

Miners that have implemented a shadow carbon price are likely to be ahead of the game. Almost half (225) of the 500 biggest global companies by market cap either have, or are planning to introduce, an internal price of carbon. Adoption of a shadow carbon price by gold producers appears to be lower.

Two gold miners that have introduced an internal carbon price are Newcrest (mines located in Australia, Canada and Papua New Guinea) and Newmont (North and South America, West Africa and Australia). Both miners have adopted a carbon price of £25-$50 per tonne.

Wood Mackenzie analysed gold miners plans for energy efficiency, changes in their asset mix, other emission abatement actions and forecast changes in the carbon intensity of the grid. Their conclusion is that the global gold industry needs to do much more if it is to align with net zero targets limiting temperature increases to 1.5°C.

Projected carbon emissions intensity of gold industry, 2019 - 2030

For those gold producers unable to change their emissions intensity, the other thing they can do is try a makeover. One way that some gold miners can do this is by transitioning to mining more copper and silver, in turn burgeoning their green credentials. Although pure gold deposits can be found in nature, it is much more likely to found in association with ores of copper. As well as lowering the overall cost profile of the mine, the ability to sell both a precious and an industrial metal can reduce the revenue risk since they typically (but not always) move in opposite directions.

What does it mean for the price of gold?

The prospect of gold mining divestment holds some similarities with coal’s recent history, but it’s not the whole story, and here investors need to careful about drawing the same connection regarding the potential impact on the gold price.

Unlike consumable commodities such copper and coal, gold exhibits a large discrepancy between the total available supply and annual additions from miners. The relationship between total supply available from inventories and annual production is known as the stock-to-flow ratio.

While the entire amount of gold ever mined totals approximately 190,000 tonnes (the stock), annual production is about 3,500 tonnes or 1.8% (the flow). If you divide the stock by the flow you get a stock-to-flow ratio of ~ 55 years.

According to the US Geological Survey, the largest annual increase in gold production occurred in 1923, which when compared with the stock of gold at the time equates to a 1.5% increase in the gold stock. The largest percentage increase in the stock of gold was in 1940 when it rose by 2.6%, and since 1942 it has never exceeded 2%.

Gold miners are powerless to change the stock-to-flow. According to Fergal O’Connor, Lecturer In Finance at Cork University Business School, “The low flow-stock [high stock-flow] ratio of gold implies low market power of gold mining firms and thus an inability to significantly influence gold prices.”

Gold miners are price takers, not price setters. And so, even if ESG mandates, high carbon prices or divestment pressure did result in a sharp decline in annual gold production (as has been seen to an extent with thermal coal), gold’s high stock-flow ratio means it will have very little impact on the price of gold.