More and more companies are voluntarily factoring in an internal cost of carbon into their business.

According to CDP, the not-for-profit charity that runs the global environmental disclosure system, the main 3 reasons for introducing an internal carbon price are driving low carbon investment, encouraging energy efficiency and changing internal behaviour.

Surprisingly, navigating climate change regulations (e.g. being prepared for a future emissions trading scheme), stakeholder expectations, and stress testing investments (e.g. not wanting their capital to become stranded) feature further down the list of objectives.

The number of companies applying an internal price of carbon has increased from 150 in 2014 to 853 in 2020. A further 1,159 companies are planning to do so within the next two years. Almost half (225) of the 500 biggest global companies by market cap either have, or are planning to introduce, an internal price of carbon.

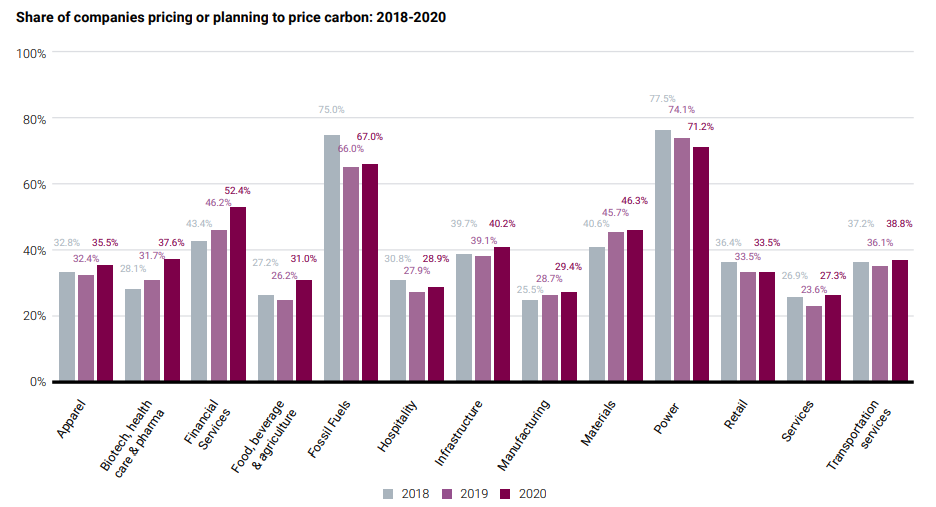

Around two-thirds of fossil fuel and power companies have introduced or are planning on implementing an internal carbon price. That makes sense given their emissions are more likely to be under scrutiny and / or subject to a formal compliance carbon market.

However, the biggest source of growth since 2018 has been the financial services sector, where the share of companies who have either introduced or plan an internal carbon price has increased by 9 percentage points to 52.4%. In Short selling is a poor hedge against carbon risk I outline the various ways that investment institutions and asset allocators are under pressure to align their portfolios with net-zero targets.

Meanwhile, the manufacturing sector has seen the lowest interest in an internal carbon price, despite it being a significant contributor to overall carbon emissions. You could argue that industry are being complacent given that free allowances are going to be gradually reduced in the EU while other compliance schemes will look to cover the sector (see Europe's steel industry yet to feel the full force of the carbon market).

The most common way companies apply an internal carbon price (accounting for almost 51% of companies with an internal carbon price in 2020), is through a process known as ‘shadow carbon pricing’. For example, a copper miner might assume a certain carbon price into its capital spending plans, perhaps to ensure that it remains profitable in the event that they are subject to a carbon price, or that there will be a market for the copper as the EV transition gathers pace. Importantly, no actual financial flows occur when companies use shadow carbon pricing.

An alternative approach, known as an ‘internal fee carbon price’ (~15 of companies) does result in actual financial flows. This imposes an internal fee on carbon emissions which can be applied to operational decisions. The revenue from the internal fee is sometimes used to establish a low-carbon fund or is simply re-distributed in the company.

Other methods used by companies include using an implicit price (calculated retroactively and is based on how much it costs a company to implement projects linked to emissions reductions), an internal carbon trading (trading carbon allowances between divisions in the similar way to a country-wide cap-and-trade scheme), and the use of carbon offsets.

CDP’s analysis found that the median internal carbon price reported in 2020 was $25 (~€22) per tonne. That compares favourably to the average carbon price in the EU ETS during 2020 of €25.5 per tonne. What we don’t know yet is whether companies have increased their internal carbon prices in line with the surge in EU carbon prices - which averaged €54 per tonne in 2021 and ~€85 per tonne so far in 2022 (see The path to a global carbon price: Why carbon markets will converge and become increasingly correlated).

The carbon price used varies significantly across different internal carbon price approaches with shadow carbon pricing typically using the highest value. Firms often use a uniform carbon price, but many also use a different (often much higher) carbon price for other parts of their business operations.

Companies based in Europe and Asia reported the highest median price ($28), followed in third place by North America ($23). The internal carbon price was lowest in Africa and Latin America ($8). At $82, apparel companies reported by far the highest median carbon price of all the sectors applying an internal carbon price.

Finally, it’s not so much the approach or the price that is important but the scope of the emissions covered that drives change, and enables companies to properly manage risk. While Scope 1 emissions are relatively straightforward to measure and report on, it is much more challenging to measure and report on indirect emissions under Scope 2 and 3.

Those same challenges means that it is easier for firms to subject Scope 1 to an internal carbon price. In 2020, over 89% of companies disclosing data on their internal carbon price to CDP identified Scope 1 emissions as being covered. There has been an increase in companies accounting for Scope 2 and 3 emissions but they remain in the minority. That will have to change as companies come under pressure to account for their entire carbon impact.