What RWE's 2030 coal burn phase out means for carbon prices

Last week German energy giant RWE announced that it will phase out the burning of coal by 2030, eight years earlier than agreed under Germany’s Coal Phase-Out-Act. The move to bring forward the phaseout means that ~280 million tonnes of CO2 will not now be emitted.

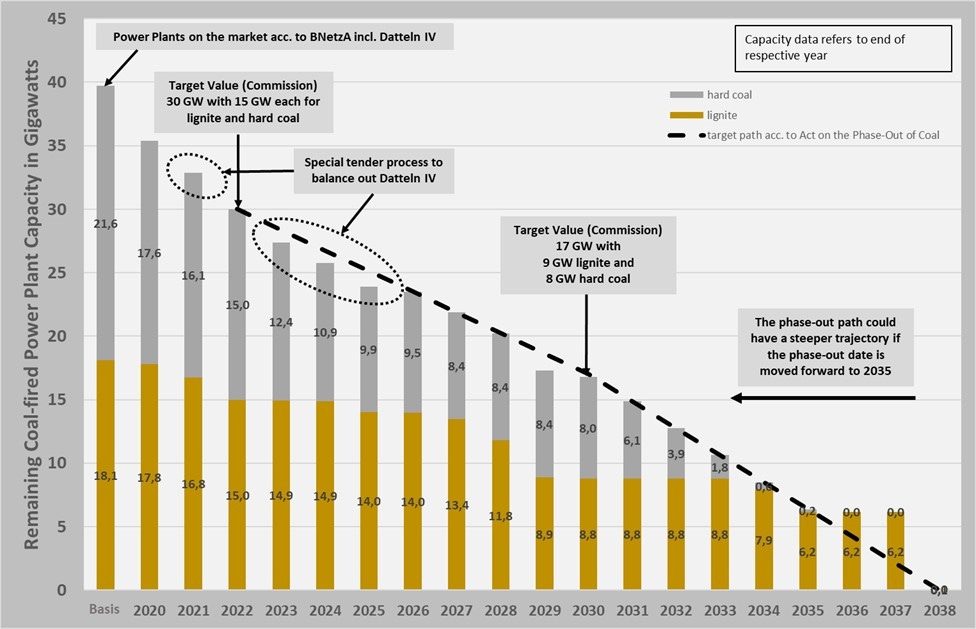

The Act, passed in 2020, outlined a trajectory for phasing out coal-fired power generation in Germany. Hard coal-fired power plant capacity would be cut from ~18 GW in 2020 to zero by 2035. Meanwhile, lignite-fired capacity would see a more gradual decline, falling from ~18 GW in 2020 to ~6 GW around 2035-37 before finally closing before the end of 2038.

Bringing that timetable forward eight years has to be bearish for carbon prices, right?

Proposed coal-fired generation capacity phase-out path (Coal Phase-Out-Act)

Despite the governments best laid plans, coal-fired emissions will still rise in the short-term as Germany burns coal for energy security reasons (see Back to black?). Two of RWE’s lignite-fired power plant units - previously scheduled to go offline at the end of 2022 - have been granted permission to continue to operate until the end of March 2024.

LEAG is the largest power plant operator in eastern Germany and the other major coal plant operator in the country. Unlike RWE, LEAG has not committed to exiting from coal earlier than 2038. The structural economic challenges in eastern Germany are much greater, meaning that bringing forward the phaseout could bring significant social issues.

Both utilities have announced plans to invest in Germany’s green energy transition, including boosting it’s solar and wind generation capacity and investing in gas-fired power plants capable of burning hydrogen. The pivot to green energy by German utilities will hopefully mean that a greater percentage of the EU’s energy needs are generated by renewable sources and serve to accelerate the decarbonisation of industry.

What impact will Germany’s coal phaseout have on carbon prices?

The impact of bringing forward the closure of Germany’s coal fired generation plants on the overall supply-demand balance for EU carbon allowances is more nuanced than it first appears.

First, the move to phase out coal by 2030 is likely to have a bearing on RWE’s carbon hedging strategy. Given it’s huge carbon footprint, RWE has been one of the most active utilities in hedging it’s future EU ETS compliance needs. Beginning in 2014, RWE began shifting its procurement strategy to buying EUAs in advance of the year that they were required. Recent figures suggested that the company had hedged its carbon exposure all the way out to 2030 (see Hedging carbon risk).

Yes, there will be more emissions over the next couple of years as some lignite-fired generation helps to negate the loss of Russian natural gas. However, moving forward RWE’s hedging strategy is likely to mean it will wind down it’s purchase of physical EUAs. Afterall, if everything goes to plan, it won’t need to hedge any carbon emissions post 2030. That points to a bearish headwind for EU carbon prices.

However, an amendment to Germany's emissions trading law, which translates the EU ETS into national provisions, stipulates that the German government will cancel the amount of EUA’s corresponding to the additional emissions reductions caused by the shutdown of coal power capacities, insofar as they are not withdrawn by the Market Stability Reserve (MSR). This means that the supply of emission allowances available will be reduced by an amount corresponding to the shuttered power plants.

In short, the loss of EUA demand for hedging purposes is negated by a corresponding withdrawal in the supply of EUAs. Overall then, what at first appears to be a bearish headwind for EU carbon prices is actually more likely to be broadly neutral.