Repost: The great sulphur dioxide allowance bull market

What lessons can we learn from the first cap-and-trade system?

As the EU carbon price hits the symbolic €100 per tonne mark there has understandably been a spike in interest in carbon markets and lots more Carbon Risk subscribers to boot.

Given the surge in interest I thought it would be a good idea to revisit one of my first articles on Carbon Risk, one that goes back to the origin of the cap-and-trade approach that underpins the EU emissions trading scheme and other schemes like it around the world.

The United States sulphur dioxide (SO2) allowance trading system may seem like a relic from history but it was revolutionary for its time. Instead of telling utilities how they should cut their emissions through regulation or direct subsidy, the scheme helped put a price on sulphur emissions and then it was left to the market to decide how best to achieve emission reduction targets at least cost.

It was technology agnostic. Very different to the situation we find ourselves in today, especially in the US where the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) seeks to direct subsidies to particular decarbonisation technologies.

The SO2 allowance trading system also offers a cautionary tale in the power of trust and the fine line that governments must tread if environmental markets are to be successful in achieving their objectives. The term I coined to make sense of this, ‘The Currency of Decarbonisation’, comes directly from reading the economic history of cap-and-trade markets and the SO2 market in particular.

The EU’s carbon market was not the worlds first cap-and-trade system to tackle a serious environmental problem. That honour goes to the United States sulphur dioxide (SO2) allowance trading system.

Flue gas emissions from coal-fired power generation released huge quantities of sulphur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions high into the atmosphere. They weren’t the only source of these chemicals, but they were by far the most important.

By the late 1980s, there was growing concern in the US and other countries that SO2, and, to a lesser extent, NOx was reacting in the atmosphere to form sulfuric and nitric acids. These acids were particularly damaging to forests and aquatic ecosystems. The problem became known as “Acid Rain”.

The first cap-and-trade market

In response to this threat, the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 (CAAA) were signed into law. Title IV of the CAAA established a cap-and-trade system for SO2 pollution allowances. At the time, putting a price on the right to pollute was seriously controversial, but it formed the foundations of what we now recognise in the EU ETS and other cap-and-trade systems around the world.

The objective of the policy was to reduce total annual US SO2 emissions by 10 million tons relative to 1980. Phase I (1995–1999) required significant emissions reductions from the 263 most polluting coal-fired power plants. Phase II, which began in 2000, placed an aggregate national emissions cap of 8.95 million tons per year on approximately 3,200 power generation units. This cap represented a 50% reduction in emissions from 1980 levels.

Between 1990 and 2004, SO2 emissions from US power plants fell by 36%, even though electricity generation from coal-fired power plants increased by one-quarter over the same period. The program’s long-term goal of reducing emissions to 8.95 million tons was achieved in 2007, and by 2010 emissions had declined further, to 5.1 million tons.

At $2,000 per ton, the scheme had a particularly onerous fine for non-compliance (i.e. levied on emitters not purchasing a permit to account for each tonne of SO2 released into the atmosphere by the time of compliance). The high statutory fine and continuous emissions monitoring meant that compliance was close to 100%. But as we’ll see it began to have an important side-effect once the supply of allowances was perceived to be in serious deficit.

The SO2 allowance market was a major success in cutting emissions

Overall, the program delivered emissions reductions more quickly and much cheaper than expected. The cost savings from letting the market put a price on SO2, versus a command and control regulatory approach, were estimated to be between 15% and 90%.

Technological innovation and the speed with which the market matured (the prospect of paying $2,000 per ton hastened the rapid learning curve of participants), were two key factors in the success of the scheme. However, a major component was the acceleration of input substitution by generators from high to low sulphur thermal coal.

This trend was already in place before the SO2 cap-and-trade system came into being and was the result of unrelated policy changes. Deregulation in the rail industry in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s led to a reduction in rail transport costs, which in turn resulted in the increased competitiveness of low sulphur thermal coal.

Some estimates suggest that about one-third of SO2 emissions reductions in the early years of the SO2 trading program were the result of lower freight rates enabling power plants to switch to low sulphur coal, with the remainder due to the SO2 allowance trading program.

What happened to the price of SO2 allowances?

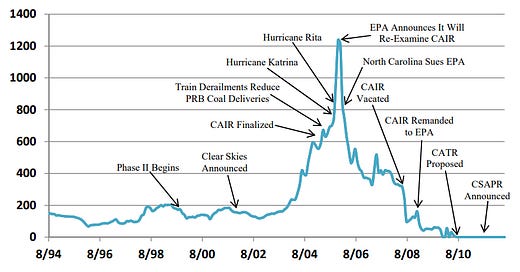

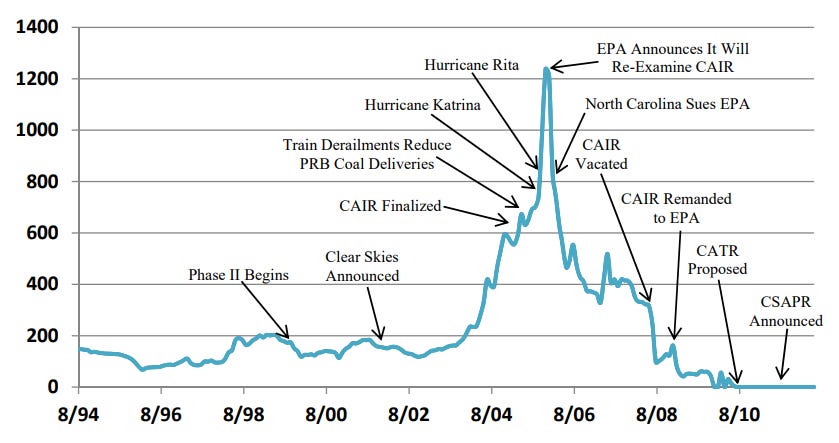

The price of SO2 allowances during the first few years of Phase I (1995-99) were relatively stable at around $100 per ton. As Phase II began the number of emitters caught up in the scheme widened significantly, and with it a more aggressive set of emission cuts. This pushed SO2 allowance prices up towards $150-$200 per ton.1

By the late 1990’s and into the 2000’s it became apparent that the level of ambition outlined in the Title IV of the Clean Air Act was insufficient to counter the high societal cost of sulphur dioxide emissions that was beginning to come to light (e.g. significant adverse health effects from fine particulates). However, there was no authority within Title IV by which the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) could impose more stringent cuts to the cap.

Chart 1: SO2 Allowance Prices and the Regulatory Environment, 1994-2012 (1995 $ per ton)

The Administration of George W. Bush enacted its Clean Air Interstate Rule (CAIR) in May 2005 with the purpose of lowering the cap on SO2 emissions to 70% below the 2003 emissions level. In effect they were trying to massage existing legislation to make up for the absence of a mechanism elsewhere in the policy rulebook.

CAIR did this in part by applying more stringent emission requirements on states that were contributing to violations of EPA’s primary ambient air quality standards for fine particulates in the eastern United States. This meant that emitters in those states had to surrender two additional SO2 allowances for every ton of SO2 emissions. This had the effect of cutting the cap by two-thirds.

Since CAIR allowed emitters to bank SO2 allowances for use in the new program, prices rose in anticipation of the more stringent emissions cap. SO2 allowance prices increased from $273 per ton in EPA’s 2004 auction to $703 per ton in the 2005 auction, before rising further to more than $1,200 per ton by May 2005.

Market participants who had previously easily met compliance, now nervously eyed the $2,000 per tonne fine for non-compliance. If the supply of emission allowances was as to be as severe as CAIR intended then there was a risk that some firms would have to cough up and pay a fine. As a result, the price of SO2 allowances was bid up to avoid being empty handed.

Other fundamental factors also fuelled the rise in prices. Hurricanes Katrina and Rita also supported the rise in SO2 prices as natural gas prices soared due to production curtailments. Unplanned railroad maintenance also disrupted deliveries of low-sulphur thermal coal which meant power generators had to switch to high-sulphur coal, increasing demand for SO2 allowances.

When trust is lost

“If that belief fades, then so do the markets. They do not merely dive; they dive and then they disappear.” - George Goodman, The Money Game

That was to be the peak. Over the next 5 years SO2 allowance price would drop to zero.

The collapse in prices was aided by the EPA’s announcement, in May 2005 that it would re-examine CAIR and speculation about impending legal challenge to the EPA involving a number of states and utilities. The states argued that the interstate trading allowed under CAIR was inconsistent with a provision in the Clean Air Act that obliges each state to prevent emissions that interfere with any other state’s attainment or maintenance of air quality standards.

This put the prospect of a dramatic drop in the cap in serious jeopardy. We never got to see how much of a magnet the $2,000 per tonne fine would eventually serve, or indeed whether SO2 prices would have surged past as entities scrambled to secure sufficient coverage of their current and expected future compliance needs.

Two years later, on July 11, 2008, the Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia responded by withdrawing CAIR in its entirety. This invalidates the core of prior SO2 regulation including the cap-and-trade system with unlimited trading across states. On that day the SO2 allowance price fell by two-thirds, from $315 to $115 per ton.

In July, 2010, the Obama Administration proposed its Clean Air Transport Rule (CATR) to limit annual SO2 (and NOx) emissions in 28 states, as a replacement for the CAIR. The proposed rule established state-specific emissions caps for power plant SO2 emissions, limiting inter-state trading. The rule was finalized in July, 2011, as the Cross-State Air Pollution Rule (CSAPR), allowing only intrastate trading and limited trading between two groups of states.

Without the possibility of inter-state trading the SO2 market collapsed. SO2 allowance prices in the 2012 auction fell to $0.56 per ton in the spot auction and $0.12 per ton in the seven-year advance auction.

The imposition of state-level and source-specific prescriptive regulation all but eliminated the demand for allowances. States with binding caps under CSAPR have no alternative but to reduce their emissions, whether by mandating the use of scrubbers, retiring coal-fired power plants, or setting up intrastate trading. Either way, the demand for federal SO2 allowances was virtually eliminated.

The whole episode also highlights how much progress was made through bipartisanship, and also how that can easily be taken away through political polarisation. Introduced under Republican administration and then supported through Democrat ones, the likelihood that support for a similar scheme at the federal level covering carbon now appears remote.

Finally, and most importantly the demise of the SO2 allowance market illustrates what happens when trust is lost, absolutely and unequivocally lost. As I note in an earlier article, the price of carbon allowances is ‘The Currency of Decarbonisation’. The message to policymakers is that if you lose trust in that, the market will die. Worse than that you will lose the fight against climate change.